“It’s all about improvising. Who has the sharpest verses with the most musicality and rhythm and wisdom and wit?”

That’s Alagushev Balai, a Kyrgyz interviewed thirteen years ago by the author Peter Finn. He’s describing aitysh, Central Asia’s adversarial, ad-libbed performance tradition that’s half music and half sick flow.

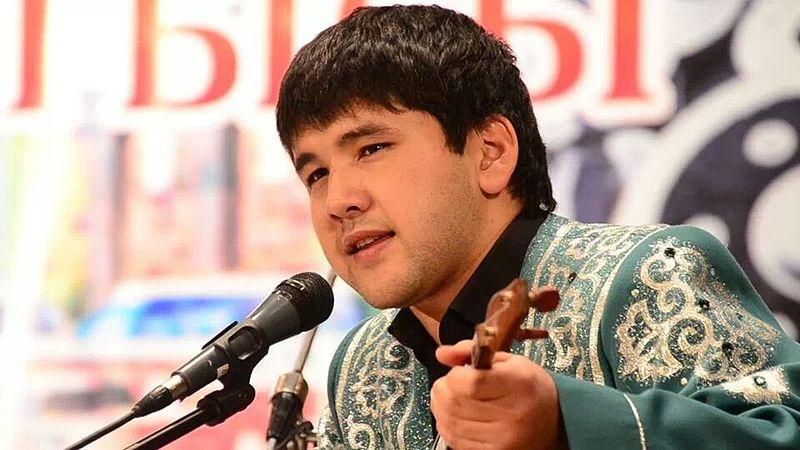

Aitysh is a contest between two participants, or akyns. They sit across the room from each other, improvising rhythmic, rhyming rebuttals on subjects suggested by the audience. Though good-natured and often comedic, aitysh has teeth. When one akyn needs to diss another, nothing is off limits: there’s a long-standing custom that allows akyns all forms of slander. They make backhanded political statements, criticise each other’s style, flirt, and flat-out insult one another.

“During an aitysh, akyns sing their songs in turns,” said Balai. “It is a musical dialogue, like a debate. When one akyn starts an argument, the second one should continue it starting a new rhyme or following the competitor’s one.”

The akyn’s goal is to convince his audience that’s he is the better performer. Just as in a rap battle, a crowd of onlookers is crucial in deciding the victor.

The tradition is artful too, and often cuttingly satirical. Politics and morals have alwasy been central to aitysh, and it’s as philosophical as Dylan, as gritty as Nas, and — sometimes — as egomaniacal as Kanye.

No one seems to know exactly where aitysh came from, but it’s been a fixture for at least a thousand years. In the pre-Soviet days of majority illiteracy, akyns played a vital cultural role. They were the agents of social and historical identity, but also helped each generation to expound its zeitgeist, celebrate its heroes and hold its leaders to account.

During the Soviet period, unusually, aitysh wasn’t entirely scrubbed from Kazakh and Kyrgyz culture, but requisitioned as a way to adapt old legends to the new rulers.

“A lot of attention was paid to akyn and the communists used it as a propaganda loudspeaker,” said Balai. “Akyns sang about Lenin and the revolution and the achievements of the party.”

It was dangerous to be an akyn in Communist Central Asia.

“During the Soviet period, akyns and their poetry were strictly controlled,” the young performer, Aaly Tutkuchev, told author, Elmira Köchümkulova. “The KGB told them to write down the text of their poetry before they went out to sing in front of people.”

So tightly did aitysh come to be associated with communism, that by the collapse of the Soviet Union the akyn art was almost extinct. According to Finn, Kyrgyzstan had only four akyns left in 1991. An influx of Western music — some of it, let’s hope, from Queensbridge and Compton — gave aitysh all the cachet of morris dancing and oompah.

As the new nation states matured, however, young people began to rediscover the tradition. Across the board, by the early 2000s, Central Asia’s cultural heritage gained a new importance. In 2003, UNESCO added the akyns to its list of intangible cultural heritage. In 2001, Kyrgyz public figure, Sadyk Sher-Niyaz, established the Aitysh Public Fund, a charitable organisation that publicises the art and has trained over a hundred new akyns.

Now, Kyrgyz and Kazakh akyns participate in the democratic political process — passing from village to village to deliver a commentary, soapbox-style.

“Akyns have always given heart to the Kazakh people in times of hardship and misery,” Kazak akyn, Didar Qamiev told the researcher, Jangül Qojakhmetova. “During the Great Patriotic War, in 1943, an aitysh in Almaty raised people’s spirits and hopes. Contemporary aitysh enlighten people and enrich them spiritually.”