Baghdad – A City of the Silk Road

By the river of Tigris, home of the mythical merchant and sailor Sinbad, Baghdad was at the heart of a complex network of trade routes and markets: the Silk Road. This is represented in the various sources and destinations of the trade activity of the city including China, India, Ceylon, Japan, Korea, Russia, Sicily, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Samarkand, Egypt, Eastern Africa, Yemen, Hejaz. But how this metropolis emerged from the sand of desert to be one of the capitals of the Silk Road in the medieval age?

Ambition of the Abbasids

The history of Baghdad (also known as Madinat al-Salam, the City of Peace or Round City) starts with an assassination and ends with the downfall of the Assassins.

After Omar, the Great had been assassinated by a slave, one dynasty rose to power from the escalating conflict: the Umayyads. As they gained most of their support from Syria, they moved the capital of the Caliphate from Medina, the Islamic religious centre, to Damascus. The House of Abbas, opposing the Umayyads, retired to Persia to wait for the right time to overthrow the Umayyad rule.

This moment has arrived with Abu Abbas Abdullah who founded the Abbasid dynasty as the ruler of the Caliphate. His successor in power was his brother, Jafar Abdullah al-Mansur, who extended the rule of the empire to Persia, Mesopotamia, Arabia and Syria. To represent the triumph of his dynasty, he wanted to create a new capital, close to his Persian allies somewhere at the heart of his empire.

As he sailed down the Tigris to find the perfect place, he was advised of the most suitable location by Nestorian monks, who had lived there earlier than Muslims. Abundance of water and the possibility of control over strategic and trade routes of Tigris determined the location of the new capital: it was established on the coast of Tigris at the point where it is the closest to the Euphrates, the other main river of Mesopotamia. These two rivers linked the city to north with upper-Syria and Asia Minor, and south with the Gulf of Basra and further to India. It faced east towards the Iranian plateau and Central Asia. Therefore, it is not surprising that according to ninth-century Arab geographer and historian Yaqubi, author of The Book of Countries, the position of Baghdad on the Tigris close to the Euphrates gave it the potential to be “the crossroads of the universe”.

It is the ambition of the Abbasids which erected Baghdad’s towers and walls and tempted merchants and adventurers to its bazaars and ports. This is the city from which mythical hero Sinbad set sail and where some of the tales of A Thousand and One Nights takes place. But how did the scene of Arabian Nights look like?

Inside the circle of flames

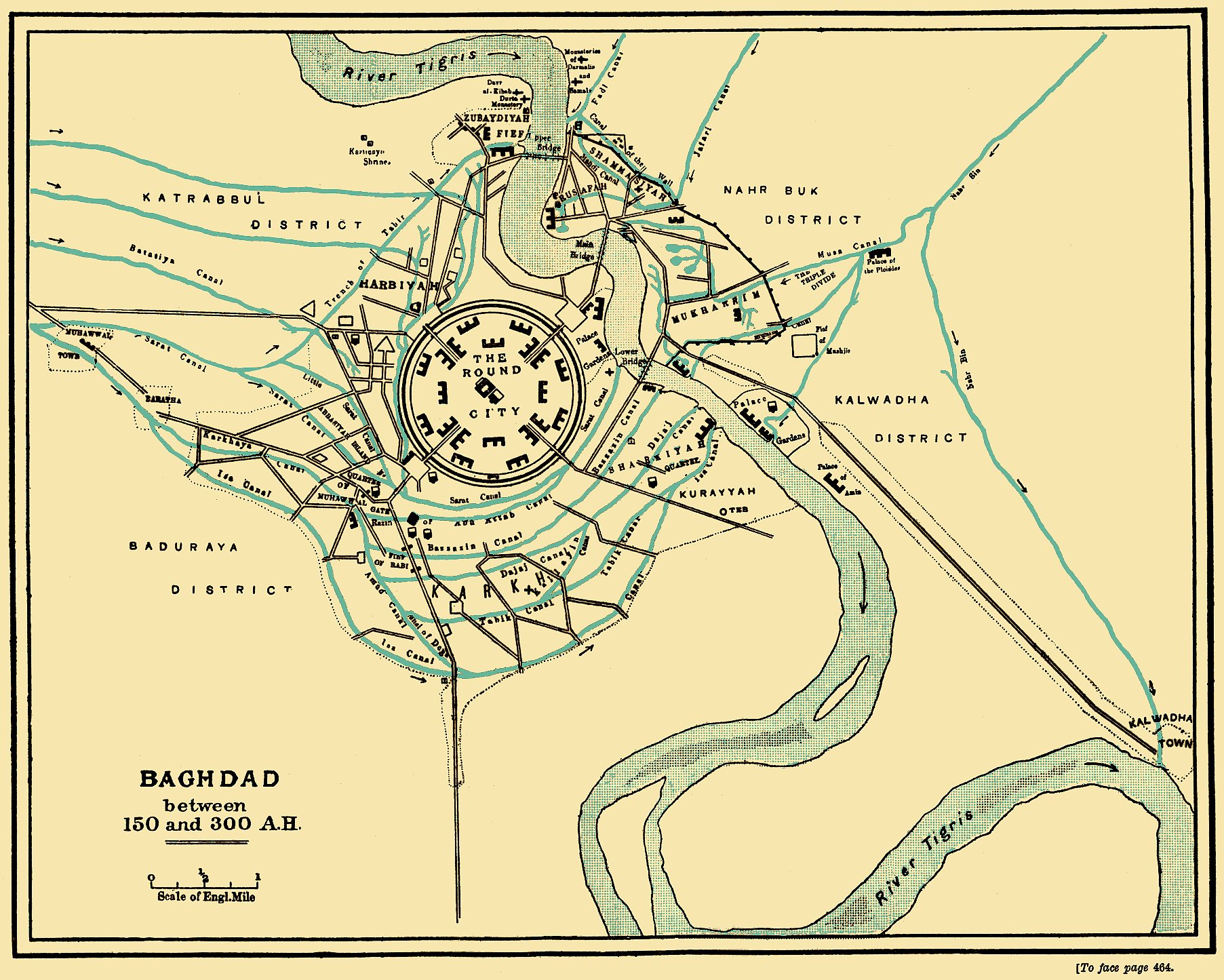

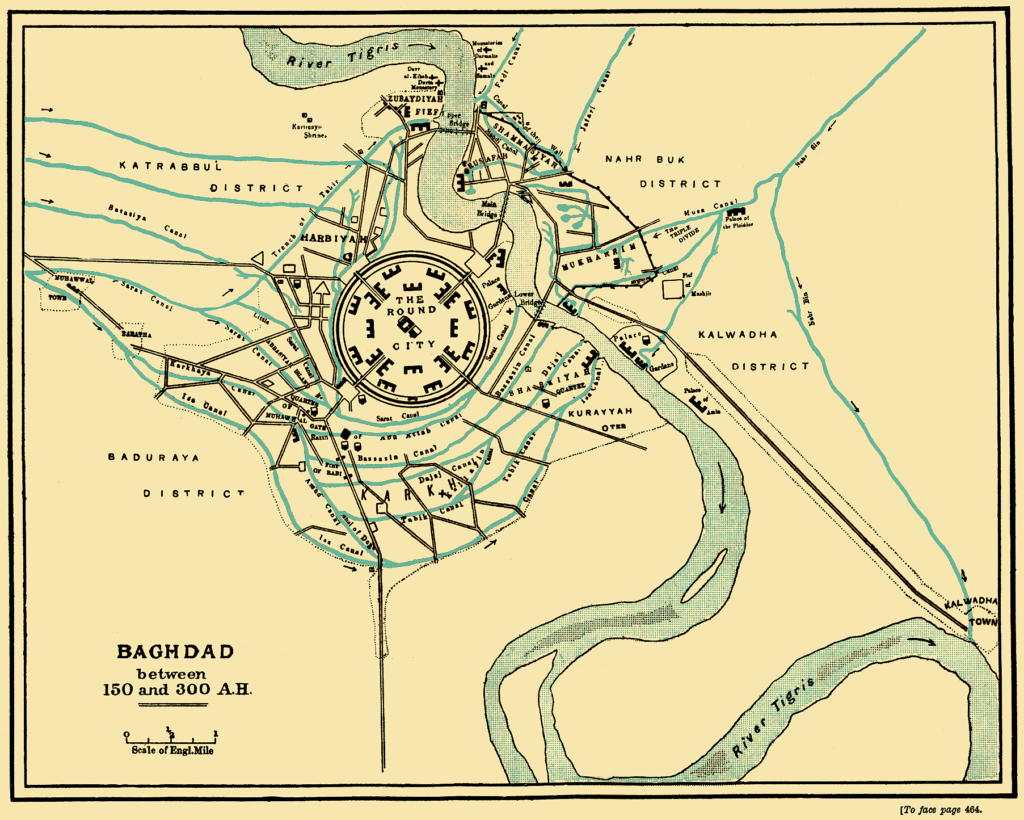

Reflecting Persian and Sasanian urban design, the city was built in a circle surrounded by walls. Construction works started on 30 July 762 as royal astronomers predicted this day as the most favourable for building work to begin. Mansur supervised the whole procedure rigorously: to ensure the most precise work he placed cotton balls soaked in naphtha along the layout on the ground and set alight to mark the position of double outer walls. Being around a circle three miles in diameter, it was constituted by two-hundred-pound blocks of stones in a height of 90 feet and width of 40 feet. As Yaqubi mentions, 100,000 workers got involved in the construction process.

The round design was unique in that time and it proved to be effective: four equidistant gates led to the city centre through straight roads. The four gates are: Khorasan Gate to the north-east, Sham (Syrian) Gate to the north-west, Basra Gate to the south-east and Kufa Gate to the south-west. Kufa and Basra opened at the Sarat Canal, a key part of waterways that drained the waters of Euphrates into the Tigris. Sham Gate led to the main road to Anbar, and across the desert to Syria. Khorasan was close to the Tigris and ensured the connection with boats on the rivers.

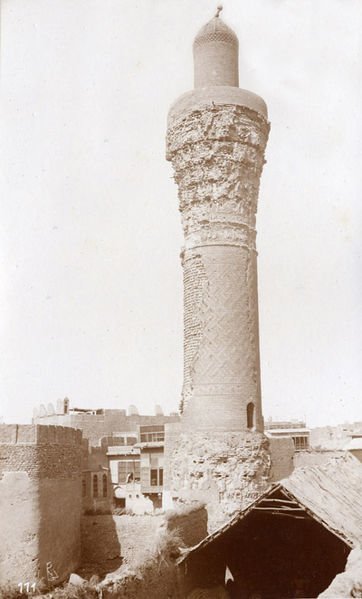

The main roads starting from the four gates leading to the city centre were connected with arcades crowded by shops and stands of merchants from all along the Silk Roads. However, the heart of the city was a royal preserve with the Great Mosque and the caliph’s Golden Gate Palace an expression of the union between temporal and spiritual authority. Only the caliph had authority to ride within this area. His palace rose above the buildings with its emerald-coloured dome in 130 feet high, nicknamed ‘The Green Dome’.

As the city expanded with bazaars and shops settling outside the walls, Al-Karkh district was formed at the south. The prospering city reached its zenith in the eighth and ninth century where poets, scholars, philosophers, theologians, engineers and merchants raised the intellectual and economic of the city. Wealth poured from every corner of the world to its market and buildings, erected high above the desert and the waters of Tigris. Its library had the largest repository of books which later could be the ground of the great achievements of Arabic and European science.

Hülegü and the end of an era

In the tenth century, caliph Mu’tasim moved the centre of the empire from Baghdad to Samarra, and the once centralised empire began to demolish. Baghdad has never reached that status it had under the early-Abbasids.

It was 1257 when the greatest political event first reached Baghdad – the Mongols. In September, Mongol Hülegü Khan sent an ultimatum to the caliph bidding him to surrender himself and demolish the outer walls of the capital. As the caliph rejected, the Mongol conqueror set forth to punish the city. He arrived to Baghdad in January 1258 and defeated the city in a month, which fell to the Mongols. Baghdad faced massive destruction of its buildings and massacre killing 800,000 of its inhabitants.

This is how the medieval glory of Baghdad passed away. It later suffered from Tamerlane and the war of two nomadic Turkic clans, the Black Sheep and the White Sheep. From 1534, after hundreds of years of Ottoman rule, the city became able to develop rapidly again in the twentieth century, but that is another story.