Farrukh Negmatzade, ‘Women behind trees’ (Image: Redwood Art Group via flickr)

In modern-day Tajikistan, artists choose to celebrate the natural beauty of Tajikistan and the richness of its traditions. With very few exceptions, contemporary Tajikistan artists rarely touch upon the complicated topics of the past and sensitive matters of the present. Most crucially, there are almost no works that commemorate or reflect on one of the most important events in the country’s modern history: the Tajikistan Civil War. This striking absence of Civil War depictions is likely due to the taboo that the Tajik State has cultivated around the Civil War’s commemoration.

The Civil War in Tajikistan, spanning from 1992 to 1997, was a brutal conflict that arose from a complex mix of political, ethnic, and regional tensions in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s dissolution. The war saw the secular government, led by President Rahmon Nabiyev and later Emomali Rahmon, pitted against the United Tajik Opposition (UTO), a coalition of Islamist and democratic factions.

This devastating conflict claimed tens of thousands of lives, led to mass population displacement, and left the nation’s infrastructure in ruins. It took international mediation and a power-sharing agreement in 1997 to finally bring an end to the hostilities.

There is, however, a notable disparity between the importance of the Civil War to the Tajik society and the mere absence of visual art dedicated to this topic. The works of well-known contemporary Tajik artists, such as Farrukh Negmatzade, Eraj Olimov and Olim Kamalov, are almost exclusively focused on non-political themes, such as Tajikistan’s nature and traditional rural life.

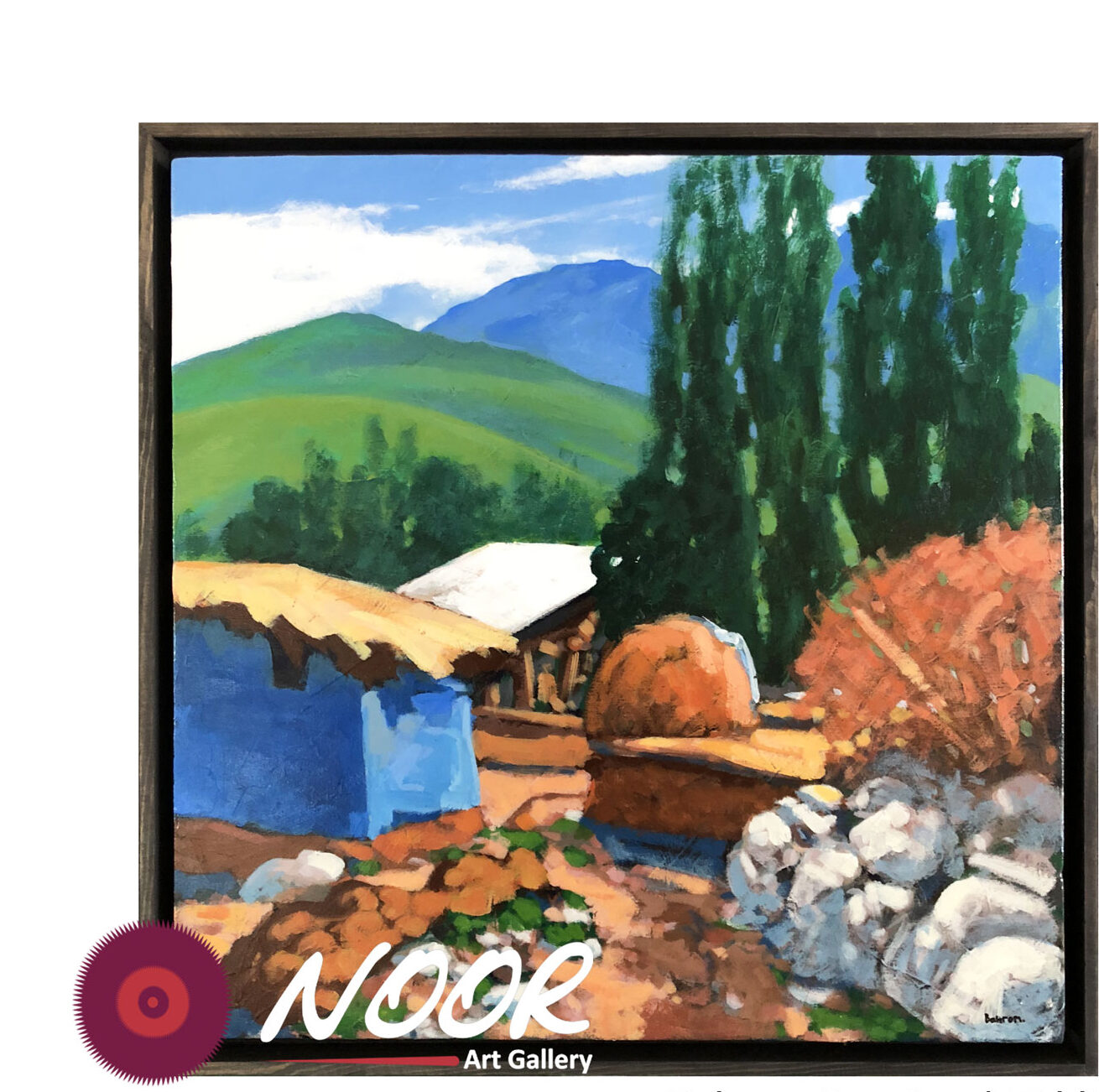

The works of Bakhrom Ismatov, a renowned contemporary Tajik artist, illustrate this trend well. In his paintings, Bakhrom depicts Tajikistan landscapes, women and men dressed in traditional clothes, and peaceful and soft colours of Tajikistan towns and villages. Similar to other prominent Tajik painters, Bakhrom does not address the subject of war.

Bakhrom Ismatov, “Ziddi”, 2018 (Image: NOOR Gallery)

An exception that proves the rule is the “Black and White” painting series by Sabsaly Sharipov. In this series, Sabsaly uses a sharp, discomforting painting technique and dark colour palette highly unusual to Tajik contemporary art. According to Sabsaly, the five paintings of the series illustrate the chaos and suffering of the Tajik Civil War that the artist has witnessed himself.

Sabsaly Sharipov, “Black and White” Poliptikh (Image: MONEE Gallery via Facebook)

While some experts, including a prominent collector of Tajik art Julia Verbitskaya, argue that the works of several other artists, such as Rahim Safarov, have likely been inspired by the Civil War, the “Black and White” series stands out as the only major artwork dedicated explicitly to the topic of the Tajikistan Civil War. Although many artists have been personally affected by the conflict, contemporary Tajik art generally avoids commenting on any politically sensitive topics, including the Civil War.

This discrepancy can partially be attributed to Tajikistan’s political climate. Tajikistan is a highly centralised authoritarian state with limited freedom of speech. Furthermore, the commemoration of the Civil War is actively discouraged by the state, and political and social commentary is often associated with high personal risks.

After the end of the Civil War in 1997, the victorious People’s Democratic Party of Tajikistan and its leader Emomali Rahman consolidated power. Although the United Tajik Opposition was initially guaranteed 30% of seats in the parliament, President Rahmon quickly initiated political prosecutions against his opponents, establishing total control over the country.

In Tajikistan, crucial power resources and wealth are concentrated in the hands of President Rahmon and his family. Civil rights and political freedoms are severely restricted. The state controls almost all of the media, harassing and prosecuting journalists and bloggers who report on social problems and criticise the regime. Over the last decade, the state has also imposed harsh surveillance to deter public discussion of salient political issues on social media.

This restrictive environment has had a direct impact on the remembrance of and the critical reflection on the Civil War. The Government has discouraged any official commemoration of the events. In the absence of plurality in politics, the state controls the narrative about the war, putting ‘national unity’ and ‘peace and stability’ at the centre of the official narrative, and overstating the role of President Rahmon in establishing peace.

Admittedly, it could be that the events of the Civil War are too recent, and the Tajik society is not yet ready to approach this topic as it is too divisive and painful. There are few films set in the Civil War period, and the Civil War is not a common topic in Tajikistan music, even among those who migrated from Tajikistan.

Interestingly, Sabsaly Sharipov does not seem to have faced any pressure from the state after commenting on the Civil War in his “Black and White” series. On the contrary, the series is currently owned by the National Museum of Tajikistan. This might suggest that, over time, the Civil War could emerge as a more prominent theme in Tajik art, even within the confines of the current authoritarian regime. However, it is likely that political factors – the risks associated with the discussion of politically sensitive topics, and the state control over the Civil War narrative – have contributed to the current taboo on the depiction of the Civil War in art.

When the new National Museum of Tajikistan opened in 2013, references to the Civil War were omitted from the exhibition. Given this notable exclusion and the current political climate in Tajikistan, it is understandable why the majority of artists might seek to avoid the risks that accompany social commentary and instead focus on neutral topics, such as nature and traditional customs.

The absence of artworks dedicated to the Tajikistan Civil War reveals the remaining scars of the Civil War, the oppressive characteristics of the authoritarian regime, and the ingrained taboo surrounding discussions of this tumultuous period.