Fashion designer Jenia Kim has established a visual language which blurs the boundaries of Korean, Uzbek, and Soviet identities. Born to a Koryo-saram family in the Uzbek capital, Kim moved to Russia at a young age before studying at the Carl Febergé College of Decorative and Applied Arts in Moscow. Through the visual aesthetics of her art, as well as the materials from which they are made, she engages in a discourse on the fragmented nature of her own identity, as well as that of ethnic Koreans in the post-Soviet space. She has referenced in the past a desire to use her work to create a particular Koryo-saram national dress, using fragments of different cultural origins to express the complicated and colourful history of her community. Rather than simply reproducing aspects of traditional Uzbek or Korean style, Kim chooses to repurpose them, merging them with modern minimalist designs. In doing this, she creates garments in which cultural references are layered, interacting in harmony. The influences which inform her collections speak to the malleable nature of self-perception, as she explores both her own personal history and the nature of post-Soviet identity.

The Korean elements of her earlier collections are particularly striking. From the inception of her brand J. Kim in 2014, she has been interested in not only embracing the cultural heritage of her community, but reinterpreting it. This practice of adapting traditional elements continues in her more recent work. In particular, she deconstructs elements of the jeogori, the basic upper garment of the hanbok – traditional Korean clothing – which covers the arms and upper body.

The ribbon which would be a focal point in the centre of the chest changes position, adorning either the waist or the shoulder. In later collections, the floral designs and traditional collar of a hanbok find themselves on a unisex silk shirt. National dress appears anything but static in these works. The artist distills Korean dress down to its most essential elements – the curve of a collar, the fit of a sleeve, the shape of a flower – before reimagining them as integral elements of modern minimalist designs. Her family, originally peasants from the Soviet Union’s far east, were internally deported as part of Stalin’s forced migration of ethnic Koreans in the 1930s. Fearing their ties to the Japanese – with whom the Soviet Union was engaged in a territorial conflict – many Koryo-saram were uprooted to Central Asia. Her designs are a testimony to the uniqueness of her cultural heritage – distinct from both Uzbek and Korean culture in terms of language, food, and dress, and yet heavily influenced by both. Combined with this homage to personal history is a trend towards urban streetwear. Decorative bows and floral cut-outs can be found along the arms of a pale green puffer jacket from her Fall/Winter 2022 collection.

In 2019, Kim returned to Uzbekistan for six months, learning local techniques in embroidery, fabric dying, and traditional patchwork design. Her focus on the materials from which her clothes are made is evident in pieces from her 2019 and 2020 collections, which draw more inspiration from Soviet-era textile patterns and fabrics. Her use of fabrics which had been produced and dyed in Uzbekistan marked a new step in her work, while she remained faithful to the geometric shapes of previous collections. Her use of viscose – with its history in Soviet-era textiles manufacturing – links Kim and her art to a wider history of fashion in Uzbekistan. She presents Uzbekistan’s textile history as a living and immediate element of her work, as she incorporates vintage elements into modern designs.

Naive embroidered patterns, repeated throughout these collections, make reference to embroidery from the 1970s by Uzbek women, who themselves took inspiration from Bollywood films – a firm favourite of Central Asian audiences. Tashkent’s first international film festival in 1958 introduced Soviet audiences to Indian cinema, with filmmakers such as Raj Kapoor becoming cultural icons. Kim weaves through her work an abundance of references to Uzbekistan’s cultural heritage – both Soviet and more traditional. She stated in an interview with the publication Buro that, in wanting to make a collection as contemporary as possible, she uses national elements sparingly. Whilst she acknowledges the contrast between modern fashion and national dress, these elements are woven together rather than set completely apart. Her clothes therefore become a visual format to unify fragmented references, creating a new way to consider the nature of post-Soviet identity – that is, the result of merging different cultural symbols in one form. In one shirt from a 2020 collection, a shirt with a utilitarian work collar – hinting at the legacy of the Soviet worker – is also adorned with a repeated square tile pattern, which connects the piece to the Uzbekistani culture of craft.

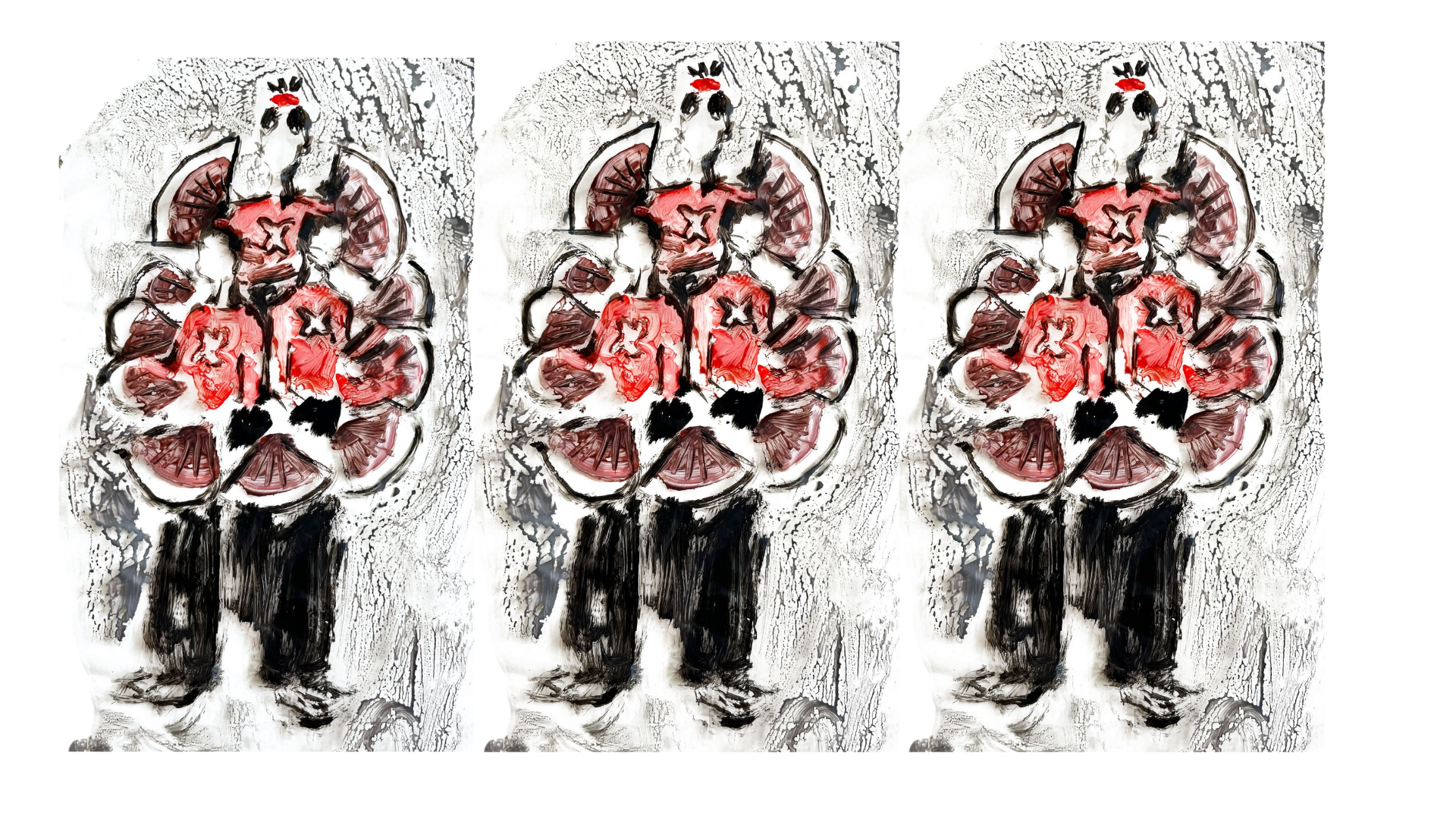

Kim tends to focus on a specific cultural practice as a starting point for a collection or project. In 2018, her Shopping at Seafood Market project led her to Jeju Island and to the culture of haenyeo – female free-divers who collect sea life to sell. Her most recent collection from Spring 2025, in collaboration with Ukrainian fashion designer Anton Belinskiy, focuses on the increasingly endangered practice of the darbozi – Uzbek tightrope walkers. Both of these projects demonstrate her willingness to re-use or adapt elements of traditional culture. Her tote bags with realistic seafood drawings are a playful reference to the clear plastic bags shoppers use to purchase fish in Jeju, whilst the flowing transparent shirts from her latest collection imitate the movement of a darboz’s flags in the wind as he inches along a tightrope.

Jenia Kim incorporates refined elements of Uzbek and Korean textile culture into garments which, though hinting at national dress, embody the simplified cut of contemporary street fashion. In re-using visual elements of personal – as well as national – history in her work, Kim creates pieces which conceive of post-Soviet identity as something constantly shifting, as she finds her origins not in one cultural realm but many.

Cover image by Joe Walford.