A story of mass movements throughout Central Asia, by Nikolai Klassen.

Not only is Russia a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma: fragments of the puzzle are also replicated and recapitulated throughout Central Asia, with the five ‘stans’ all bearing idiosyncrasies that point to a past as rich and unpredictable as the present. Let me address one such mystery: why, like myself, are there so many German-Kazakhs? Nowadays, Germans represent a sizeable minority in each Central Asian country, for example, there are still 179,476 ethnic Germans dwelling in Kazakhstan. However, ethnic Germans only began to form a sizeable chunk of Kazakhstan’s demography shortly after 1941. So, why did so many Germans go to Central Asia? And what does my grandmother have to do with this story?

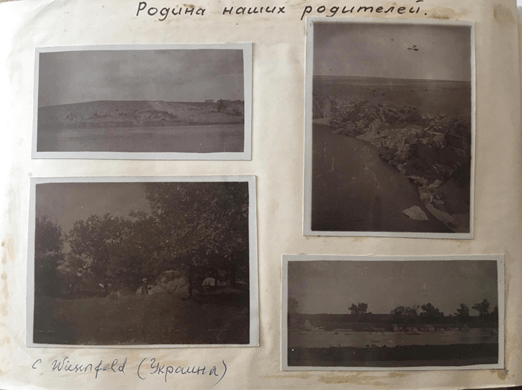

Like my grandmother’s family, many German speaking settlers moved east in search of opportunities off the back of Russia’s developmental efforts. Under Ivan II (1462-1505) some experts, such as doctors, architects, and military officers migrated to Russia. At the time of Peter the Great (1682-1725), Germans increasingly began settling along the Volga River in significant numbers. Another figure driving German Migration in Russia was Kathrine the Great. In 1762, she invited German farmers and craftspeople to Russia to help modernize her country, giving them land, religious freedom, exception from military service and tax exemptions. Escaping high taxes and political tensions in the Holy Roman Empire and later Prussia, most came to lay the foundations for new settlements. Some 30,000 arrived in the first wave between 1764 and 1767 and they had a profound impact on improving Russia’s agricultural output. More started coming after 1789 and they kept coming until 1863. Most of them were Catholics or Mennonites seeking religious freedom, a new place to settle and political stability. As they swept down to Russia’s eastern and southern borders, the first German settlers arrived in modern-day Kazakhstan by the end of the 18th century. In due course, Germans founded their first permanent settlement in 1785, called Friedensfeld. During the period of the Stolian reforms in 1905—1911, Germans had already formed towns such as Alexandertal, Altenau, Königsgof, and Puggerhof. The migration did not stop there though: German settlers even tried to reach as far as Azerbaijan in the 1930s. The reason: increasing hostility and distrust directed against the settlers due to the political climate in Germany at that time. This time, Mennonites have been suspected not because of their religion but because of their nationality.

History is rarely kind, and World War II is known for its forceful relocations within the Soviet Union. Most of the Germans were offspring of Volga Germans, who lived in the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic located in Russia, or the Black Sea Germans, who lived in Ukraine and Crimea. This demographic spread reached an abrupt ending during the early 1940s; with forced relocation to Kazakhstan being initiated in July 1941, after Hitler declared war on the Soviet Union. Moreover, Stalin initiated a state of emergency: Germans were declared spies a priori, a decision which resulted in all working-age men (15-85) being confined to Soviet Labour camps – the so-called gulags. According the Soviet Government, a decree to relocate the Germans was imposed because:

“Among the German inhabitants, who live in the Volga Region, are thousands and ten thousand of saboteurs and spies who are awaiting a signal from Germany to execute explosions in other regions, but also against their own people.“

In the course of the deportation, my granduncle and my great-grandfather were sent to two different gulags nearby Archangelsk to work in a forestry station in pitch-black winters and all-day summers. Fortunately, they were working as doctors and were important for the camps’ overseers. They were able to survive the extreme temperatures and harsh labour conditions, and were lucky not to have been sent to an even-more punitive camp, where their medical skills may not have been called upon.

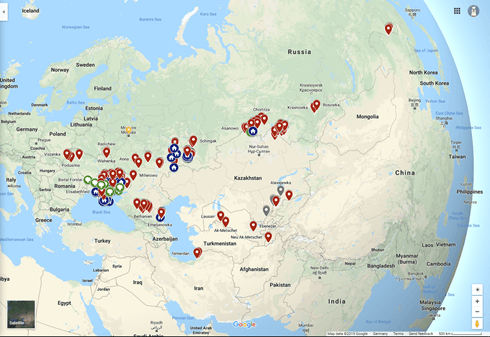

Officially, people were never deported: they were brought to safe towns, away from the frontlines. The areas to “spread” the Germans across the countries were areas, such as the Altai region (650,000 re-located), the Qaraghandy region (500,000), Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (both home for 70,000 Germans). The regions where Germans were spread generally had a low population density and a demand for workers in agriculture and mining. The labour shortage arose from the huge demand for troops to send to the Soviet frontline, leaving many Central Asian towns stripped of their male populations. As German settlers were suspected to be spies and saboteurs, the authorities saw fit to keep an eye on them and extract their productive energy through keeping them in tightly-controlled labour camps. In addition to forced labour, Germans in the Soviet Union were subject to forced assimilation, such as through the prohibition of public use of the German language and education in German, the abolition of German ethnic holidays and a prohibition on their observance in public. Not only were Germans stripped of their language and culture, they were often openly discriminated against and publicly mocked. At around this part in our story, my Grandmother, then a young girl, was making her way across the frozen midwinter Steppe in a cattle wagon. In 1941, she, her mother, and other 38 people put into the wagon were forcibly relocated to Serenda (Зеренда, nowadays in Kazakhstan).

Suppression of ethnic Germans in the Soviet Union did not end with the Second World War. Though some Germans were able to live unofficially in German communities in tows they’ve been sent to, their culture had to remain hidden: still, they were able to secretly hold holy services, speak German, and celebrate German holidays. In 1949 most Germans were finally released from the labour army, although no public apology or excuse was given for the 4-year delay. In August 1964 the Soviet Government finally began rehabilitating the Germans to their pre-war settlements. According to the newly appointed president Breshnev, the accusations against were not justified, and a terrible mistake had been made. However, most chose to stay on in Central Asia, and only a few returned to the Volga area. Others travelled around and went where they could find employment. Others still tried to claim their pre-war homes, even though they lost the right to do so. After 1964, the German population became dispersed and mobile – finding new homes and shaping new identities. The number of Germans involved in agriculture declined while those occupied as academics and teachers rose, as those living in the country moved to the cities. In that process Germans finally managed to blend into their milieu, losing their cultural uniqueness as their language, arts, customs were becoming more and more Russified. Many Germans moved in among non-Germans and started families with people of other ethnic descents. The trend towards urbanization also caused a drop in the birth-rate and the size of German families, which had been erstwhile characterized by high birth rates. By 1991 less than half of the German Russians claimed German as their first language, and instead regarded Russian as their mother tongue.

The horrors of deportation and the tragedy of Stalinist cultural subjugation became far better known through historical studies during the 1980s and 1990s, after the Soviet Union fell apart. Most of the remaining ethnic Germans emigrated to Europe and beyond, with a majority opting for Germany. In 1990, after my Grandfather returned from a visit to Canada, he and my grandmother decided to move to Germany, where they felt they would be treated as equals. From there they invited other parts of my family and finally also my father and my mother, who was pregnant with me while moving.

In 1990, there were around 2.9 million ethnic Germans in the Soviet Union, of which only 41% resided in modern-day Russia. The rest were spread throughout Central Asia and the Caucuses, with 47% being based in Kazakhstan, 5% in Kyrgyzstan, and 2% in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. As these populations either blended into their cultural woodwork, or made their way to Germany, these populations have fallen to about 1/3rd of their original size. Yet their footprint lingers on in countless aspects; so, should you ever find yourself North of Astana and notice rock-hard dark breads curiously similar to German pumpernickel, please spare a thought for my Grandmother who, like so many other Soviet-born Germans, has left a lasting mark on Central Asia’s demography.