-

How Investment into Kazakhstan‘s Education System has Impacted the National Economy

Zara Draper from the University of Cambridge explores how foreign university campuses and scholarship programs are accelerating Kazakhstan’s economic growth

-

Evaluating Central Asia’s ‘Golden Age of Arbitration’: Prospects for a New Legal Age of Commercial Dispute Resolution

James Hone, University of Cambridge, explores the development of international arbitration institutions across Central Asia.

-

The Kazakh Intelligentsia’s Role in Shaping National Identity

Ana Ross from the University of St Andrew’s delves into the history of the Alash Orda in Kazakhstan in the early nineteenth century.

-

Turksib: Awakening Central Asia

Annabel Hou, a BA student from U.C. Berkeley, analyses the imperial messaging of Viktor Turin’s 1929 film ‘Turksib’.

-

Cross-Border Connections: Nuclear Agency in late Soviet Kazakhstan

Rebecca Hawkins, a PhD student at the University of Cambridge, discusses her research on nuclear agency in late Soviet Kazakhstan.

-

Growing Activity of Russia and the EU in Kazakhstan Could Lead to Economic Conflict by 2030

Eldaniz Gusseinov analyses the growing possibility of economic conflict between Russia and the EU in Kazakhstan.

-

Decolonisation and Adaption for the Future: Language Politics in Kazakhstan

Image via Wikimedia Commons Driving down any street in Astana, Kazakhstan’s new, hyper-futuristic capital city, you may be surprised to note the total absence of any Russian-language signage. In fact, insofar as whoever is in charge of Kazakh road marking is concerned, English takes precedence over Russian, with Latin script transliterations of placenames sitting under…

-

Trading Places: The Rise of China in Kazakhstan

Image: Richard Hagues via Flickr The power dynamic in Central Asia is shifting due to Kazakhstan’s changing economic and cultural relations with both Russia and China. Historically, Kazakhstan has maintained close ties with Russia, underlined by substantial trade and cultural affinity. However, due to the war in Ukraine, Kazakhstan is moving away from long-standing Russian…

-

Turkic Winds of Change: How Kazakhstan and Türkiye are Forging a New Strategic Partnership

Photograph: Ninara via Flikr In September this year, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan travelled to Astana, the gleaming capital of the Kazakh steppe which has come to embody the ambition of the country’s leaders for the future. To many, a Turkish minister in a Central Asian city may seem to represent a relatively minor act…

-

Why can you buy German bread in Kazakhstan?

A story of mass movements throughout Central Asia, by Nikolai Klassen. Not only is Russia a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma: fragments of the puzzle are also replicated and recapitulated throughout Central Asia, with the five ‘stans’ all bearing idiosyncrasies that point to a past as rich and unpredictable as the present.…

-

Review of Overcoming a Taboo: Normalizing Sexuality Education in Kazakhstan

Recent reports show the rates of child abandonment as a consequence of unwanted teenage pregnancies are alarmingly high in Kazakhstan. This problem along with other sexual health problems could be the result of a number of factors, including the lack of effective sexuality education programs in the school curriculum that would shape young people’s sexual…

-

Europe and Kazakhstan

Former Austrian foreign minister, Dr Benita Ferrero-Waldner, outlines the growing interdependence of Kazakhstan and the European Union.

-

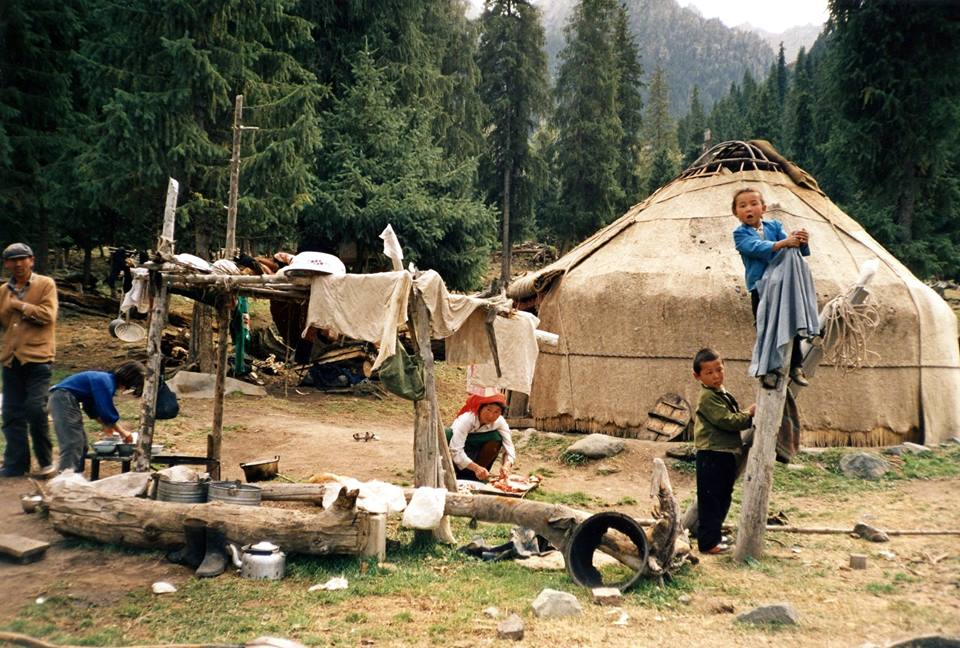

Hair-Clips and Hierarchy

What ‘Mambetka’ means for Kazakhstan in the Age of Inequality.