In 1928, Joseph Stalin initiated the First Five-Year Plan to collectivize agriculture and rapidly industrialize the USSR; one of the notable elements of this radical campaign was the Turkestan-Siberian Railway, a shock construction project that sought to bolster the national economy by connecting the grain lands of Siberia to the cotton farms of Central Asia. Released just after the introduction of the First Five-Year Plan, Viktor Turin’s documentary film, Turksib (1929), deepens the implications of this Soviet socialist project. By utilizing the familiar rhetoric of the ‘civilizing mission,’ it reflects Soviet aspirations to create a united Eurasian sphere of which Russia is the ideological heart.

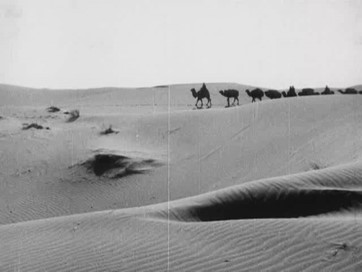

The setting of the film’s first three acts is bleak. It begins in the barren desert of the newly created Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, labeled negatively as “a land of burning heat” in which the only positive elements are the industrialized processes of cotton cultivation. Each shot drags on for an eternity as Turin constructs a seemingly slow and meaningless lethargy that permeates the land. Such ennui is amplified in viewers, who are snapped back to attention only with intertitles that appear every few minutes. By heightening the emptiness of the landscape, Turin effectively depicts the Kazakh ASSR as a backward country dependent on Sovietization: the Kazakh people are experiencing shortages and it is Russian modernization that provides grain for them. The ‘othering,’ infantilization, and stereotyping of the ‘Oriental periphery’ is a common symptom not only of older Russian Romanticism but also of the contemporaneous Soviet socialist project, which sought to mold a new proletarian body out of the diverse Central Asian peoples.

Act I opens with a stark contrast between the silent stillness of pastoralism and the lively energy of ‘modern’ civilization. The Kazakh nomads “[wait] helplessly” for water, greeted only by the rare appearance of clouds that do not spare them even a drizzle of rain. Immediately following shots of their nomadic pastoralism, however, is a quick sequence of melting ice flowing down to the land from the mountains above. Representing the modernity and industrialization that too rapidly flow into Central Asia, the rejuvenating water provides the arid Kazakh land with what is essential for survival. The film reveals how the Soviet Union saw its industrialization of the frontier as essential for the periphery’s survival, lest it be lost to the ‘primitive’ past; thus, in the narrative, the indigenous population’s life is positively transformed by Soviet intervention.

The characters sprawl around aimlessly in the first half of the film, often lost in a deep mid-day slumber. The sleeping Kazakhs in Turksib represent a somnolent frontier only to be awakened by Russian modernity. Sleep is a common motif in Russian imperial narratives regarding the Asiatic East and acts as a metaphor for supposedly unexplored and untouched land. Rich in energy resources such as oil, gas, coal, and waterpower (the construction of the Turkestan-Siberian railroad was meant to exploit Kazakhstan’s mineral abundance in particular), Central Asia was often imagined by Russia as the Sleeping Beauty whose true potential needed to be unlocked. The sleeping adults, children, and dogs of Turin’s film awaken at the arrival of the Russian trucks, and the stillness of the film is suddenly thrust into lively stamina. The stereotypical depiction of Kazakh culture, characterized by laziness and paralyzing inertia, is thus diametrically contrasted with the movement of the Russian engineers and surveyors, whose knowledge revolves around modern industry and new technologies. Additionally, when the Russian surveyors arrive in the desert, the natives are depicted crowding the trucks in curiosity and excitement, in awe of the Soviet vehicles. Kazakh children race after the trucks, implying that they are chasing modernity and leaving behind their ‘old’ village. Amidst the excitement of the youth, there is just one skeptic: an old Kazakh man who denounces the trucks as “a devil’s chariot.” Although elders are typically given the most respect due to their wisdom in indigenous Central Asian cultures, this old Kazakh man is instead caricatured by Turin as a mere relic of the archaic past.

Turin’s strongest emphasis on the dialectics of movement is made in the fourth act of Turksib, in which Kazakh equestrians chase after a Russian train. The Kazakh horses move relatively slowly through the landscape; the nomads hardly advance through the physical landscape and time threatens to leave them behind. In contrast, the steam locomotive is an unstoppable force racing through both time and geography. In Soviet media, trains are usually portrayed as positive symbols of progress, revolution, and imperial domination. The horses are ultimately unable to catch up to the modern vehicle.

Although Turksib uses dialectical montage to highlight the messianic Soviet destiny in Central Asia, it is important to note that the two conflicts that occur in the documentary are not between the Russian engineers and the indigenous Kazakh peoples, but rather between nature and civilization, and between the past and the future. The only threats that the indigenous people explicitly face in Turksib are the unforgiving elements of the environment: the Kazakhs must wait patiently for water and fight through sandstorms to transport vast supplies of grain and timber. “In the desert, the enemy is wind,” not the Russian colonizers.

As conflicts exist only between society and nature in this film, Turin suggests therefore that social harmony has already been attained. Above all, Turksib is about the idealization of united Soviet labor, in which no interethnic strife takes place. In the film, the cooperation between the Russians and the Kazakhs is what allows for the construction of this transnational railroad, pacifying nature and putting it at the service of man. This reflects the state’s attempts to create a uniquely Eurasian culture in which locals of Central Asia were incorporated into the Soviet proletariat.

Certainly, if Eurasianist ideologues define ‘democracy’ as the “participation of the people in its own destiny,” [1] then the state could certainly mark the ideological mission behind the Turkestan-Siberian Railway as a democratic project. However, it should be stressed that the Soviets envisaged such “participation” as a submissive yielding to the plans of a stronger entity– in this case, the Kazakhs’ forced acquiescence to the Soviet political project. Turin portrays the Kazakhs as eager coworkers who warmly welcome, rather than restrict, the Russians: the former accept the modern railway in their midst and do not appear to have much anxiety over its impending effects on their life. Such a narrative posits a Eurasian utopia in which socialist industrialization has removed the need for conflict.

But reality instead proved to be dystopian for the Central Asians– it was precisely this Russian ‘civilizing mission’ that would have devastating consequences for the Kazakh people. While most Kazakhs had traditionally been nomadic pastoralists, Soviet collectivization forced them to “sedentarize, to abandon the economic practice of nomadism, and this shift… [led] to very far-reaching and painful shifts to Kazakh culture and identity.” [2] Indeed, in the years immediately following Turksib’s release, Kazakhstan experienced a great famine – the Asharshylyk – that would result in the death of almost a quarter of its population. For a long time, this famine was largely absent from both Soviet and Western dialogues, with Soviet narratives of the Kazakh famine being all the more dismissive.

In contrast to the horrific realities of working along these railroad lines, the final scenes of Turin’s Turksib suggest a final subsumption of the periphery into Soviet socialism: in a poetic union of the ‘Oriental periphery’ and Russian state, a curious encounter between the primitive past and socialist modernity, a Kazakh camel sniffs the Turksib railroad. The film closes with images of “[19]30,” Central Asia, and a speeding train flashing in rapid succession, through which Turin presents a conjunction of time, space, and movement – the complete temporal and spatial integration of Central Asia into the Soviet project. The meaning encapsulated here is central to the Soviet Union’s modernist mythology: triumph over nature is measured by the progress of machinery and the labor of man, in which “civilization breaks through with mechanical equipment.”

Turksib is a masterful demonstration of Soviet montage theory, an educational and Romantic documentary meant to depict Central Asia as a site of civilizational awakening, epic collective labor, and technological divinity. But its hypnotic cinematography and sentimental aesthetics notwithstanding, such a narrative must be analyzed in the context of its creation; that is, in Russia’s ‘othering’ of Central Asian culture and history, an infantilizing trend that has persisted from the Tsarist Empire, through the Soviet Union, and until now in the 21st century.

Works Cited

[1] Aleksandr Dugin, Eurasian Mission: An Introduction to Neo-Eurasianism (London: Arktos Media, 2014), 33.

[2] Sarah Cameron, “Remembering the Kazakh Famine,”Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, 20 May 2020, https://daviscenter.fas.harvard.edu/insights/remembering-kazakh-famine.

Turksib. Directed by Viktor Turin. Vostokkino, 1929, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZSSfhArp0g.