Introduction

4am in Vršovice, East Prague. A man sits in a crowded room playing a dombra, the light is low, but he doesn’t miss as his fingers glide along the fretboard. He has been at this for hours, and yet there are no phones to capture the moment. From another room, there is a faint pulse, and I get up to wander outside. A samovar offers free cups of tea, dancers twirl, and the attendees flip between Czech, English, Slovak, Russian, Georgian, Kazakh, Tajik… On the ground a flyer is briefly illuminated, revealing that tonight we are celebrating Nowruz with artists from Central Asia to North Africa. Tonight, we are united in celebrating the new year.

Central Asian electronic music in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) is a niche-within-a-niche. Yet, joined together through a shared history of Russo-Soviet suppression of the underground, Central Asian artists are increasingly finding themselves playing sold-out shows in the clubs and warehouses around the CEE region. Their tunes represent a weaving of cultures into the fabric of the underground music scene, whilst avoiding as best they can the dreaded label of ‘turbofolk’.

The Soviet Tashkent Underground

The centre of the Central Asian music scene has long been the toi (tой), or traditional celebratory music, typically played at weddings. Musically speaking, toi is characterised by melodic improvisation, call-and-response vocals, traditional instruments such as the dombra and doyra, and a strong rhythmic drive. During the Soviet era, however, Central Asian republics experienced both periods of cultural suppression and the state-sponsored promotion of folk arts. Ensembles appeared at official events, and folk music was recorded using traditional instruments, often stylised for propaganda purposes. Despite this, toi gatherings remained largely beyond state control, and whilst they were viewed with suspicion, they nonetheless allowed for improvisation and regional styles to flourish.

Tashkent in Uzbekistan emerged as a regional music hub during this period, bolstered by an influx of World War Two refugees and the presence of the Gramplastinok vinyl pressing factory. Whilst most records were released through the USSR’s state-run label Melodiya, which made subversive music difficult to officially produce, alternative sounds still found life underground. Toi, widely listened to and operating outside official channels, became a key source for sampling and experimentation by underground music communities. The scene also drew from the region’s diverse cultural fabric, shaped by multiethnic histories and Soviet population engineering.

Somewhat surprisingly, during the ‘70s, local electronic, disco, and rock music appeared alongside Western artists and genres in legally sanctioned clubs – although dancing often had to be preceded with a lecture on the ideological superiority of socialism. After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, economic turmoil shuttered a large number of record plants, although this often coincided with the relaxation of cultural controls, giving rise to a strong DIY music scene in cities such as Tashkent and Almaty. Promoters began organising basement raves and open-air parties in repurposed warehouses and private flats, whilst pirate radio sets and mixtapes sold on the street circulated between friends.

Between Repression and Community

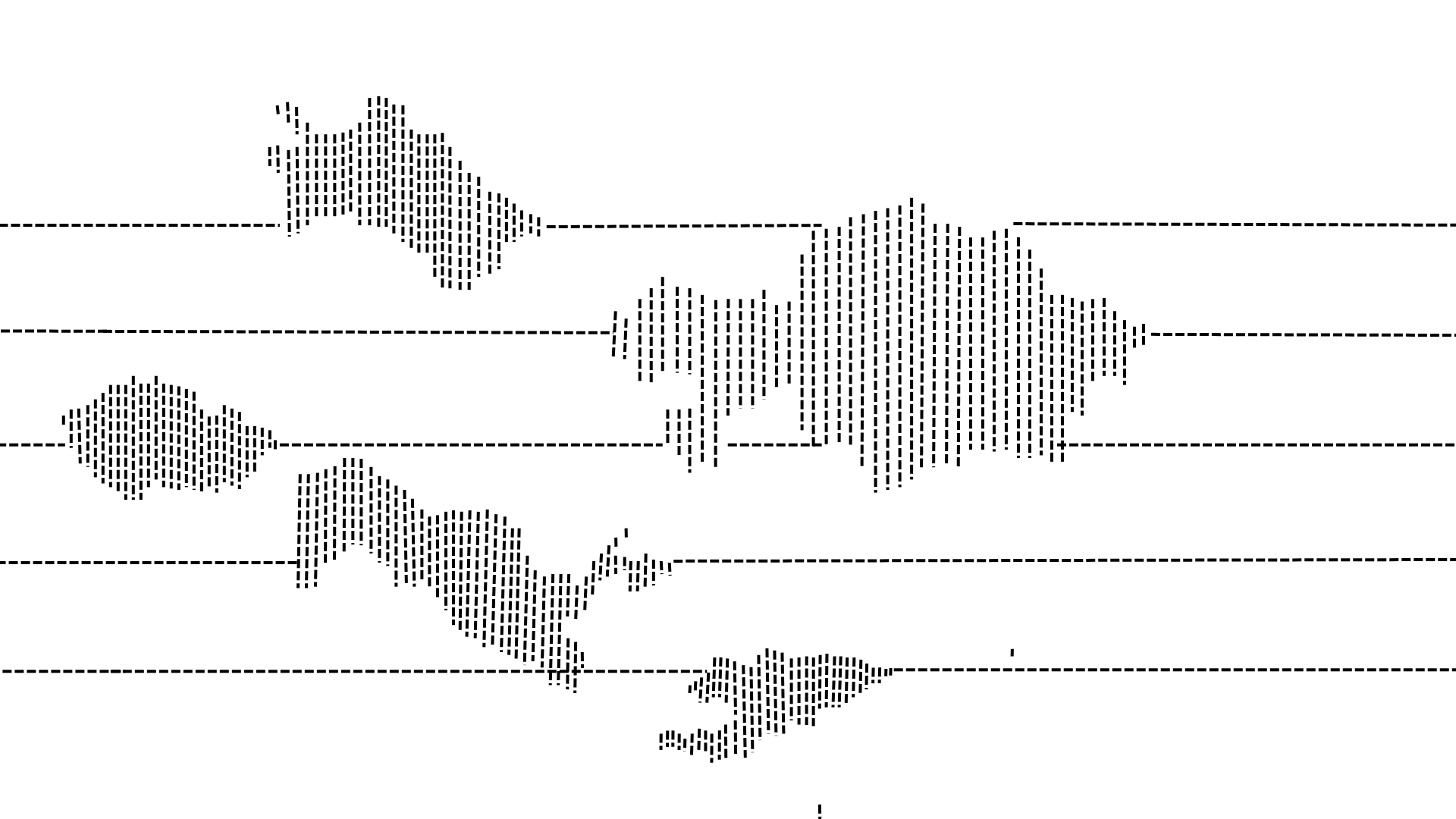

Today, the electronic music scene across Central Asia is an eclectic mix of regional centres and transnational projects. A new generation of artists, and collectives are pushing the boundaries of state repression through collaborations with events such as Boiler Room. During Sabinē’s set at the event, she began with sampling the Tanbur which gradually built into an industrial techno bassline. As the set unfolded, pounding rhythms and metallic textures predominated, before slowing right down for a track ending with a remix of a local song. The soundscape thus bridged the tonalities of Uzbekistan and the industrial techno heartland of Central Europe, to create a set which was entirely its own.

In Uzbekistan collectives such as Stihia have transformed the desert into a pilgrimage site for cutting-edge sounds and environmental activism, hosting workshops on solar-powered stage design and panel talks on water conservation. Clandestine disco reissues and field-recorded folk loops are also enjoying a renaissance. The 2023 compilation Synthesizing the Silk Roads combined rare Soviet-era disco, folk-tronica and rock from Tatar, Uyghur, Tajik and Uzbek archives into an album which Billboard lauded as ‘a revelatory window into forgotten soundscapes’. Across the border in Kazakhstan, nights at venues like República in Almaty, and showcases in Nur-Sultan show a scene that is as politically engaged as it is dance-floor driven.

Unfortunately, state repression continues to haunt artists – although care must be taken here to distinguish between countries and not to homogenise the region. In Uzbekistan, artists and musicians often contend with moral policing and restrictive licencing laws that can shut down unapproved venues at a moment’s notice. Across the border in Kazakhstan, meanwhile, artists are more likely to face erratic permit refusals and occasional club closures as opposed to outright bans. Expectedly, Turkmenistan exerts the most control over its music scene, as laws ban non-state-approved recordings and confine live performance to government-run ensembles. A quick glance at Turkmen television, however, reveals that electronic impulses can be heard running behind officially sanctioned music. The situation in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, whilst not as bad as Turkmenistan, suffers from the relative marginality of both countries. Nonetheless, in Tajikistan a number of small scale festivals carve out spaces for creativity away from repressive government interference in the country’s cultural life. In Kyrgyzstan, a small but growing scene centred around Bishkek and featuring trance music suffused with traditional instruments is slowly finding its footing.

The threads that tie Central Europe and Central Asia Together

Across CEE, Central Asian artists are bringing the sounds of their home countries to new audiences, weaving new sonic tapestries in warehouses around the region. In Prague, Temple Of has become a landmark, staging line-ups which unite post-colonial people (including Central Asians) with CEE audiences – perhaps as a sonic nod to the Silk Road. Berlin, shaped by its immigrant communities and Soviet-era Eastern Bloc ties, hosts many Central Asian performers. Experimental artists like DJ Hotsand and Kokonja have used sets to merge folk traditions with electronic music, ensuring the city’s place as a key hub for cross-regional cultural exchange.

Kokonja is a multimedia Kazakh artist who uses her family’s heritage as craftspeople as inspiration in her visual and musical practice. In her felt making she draws inspiration from traditional Kazakh yurt architecture, and her 2023 piece ‘Shelter for Rejarbo Kuepe’ was exhibited in Paris. For Kokonja, sound and physical art are two sides of the same coin, acting as ‘multigenerational tools’ to express the voices of her ancestors. Her 2023 EP ‘badik!’ also deeply engaged with the nomadic heritage of Kazakhstan. As she describes it, the release was inspired by the ‘pre-shamanic form of the spiritual oral musical tradition of nomadic tribes […] Jylyjai is on the B side, an ambient composition made of wind records’.

Listening to the album, which is available on Bandcamp and Spotify, is a dislocating experience. On ‘kөshirilgen’, cymbals rattle as breathwork in the background forms an all-encompassing wall of sound; on ‘agugigai’, synths blend with traditional instruments and drums, to gather in intensity and pace before unexpectedly falling away. The B-side, ‘Jylyjai’, stands in stark contrast to this sonic storm, offering a slow, meditative space where the natural environment itself becomes an instrument as wind generates sound through the qobyz and dombra. Despite being a smaller artist than some others discussed here, Kokonja’s work, which she brought to Berlin’s Humboldt Forum, as well as to Boiler Room in Almaty, shows how a Kazakh artist has interpreted the traditions of their home country for a European audience across a variety of media.

Konkoja is also a member of the Davra collective – a group created by the Uzbek Director and artist Saodat Ismailova which aims to ‘connect and develop the Central Asian art scene’ both within Central Asian countries, and through exhibitions in Europe. In 2022, the collective exhibited at Documenta Fifteen in Kassel, Germany. Ismailova’s production at the festival, ‘Warble with the Earth: Sound and live performance for Davra (2022)’, was an attempt at ‘loosening cultural hegemony through pieces of sound memory from her [Ismailova’s] home in Central Asia’ by combining music produced by a DJ mixer, with the Temir Ooz Komuz. As the description for Ismailova’s Kassel production notes, the Temir Ooz Komuz is traditionally played by women. Indeed, the centrality of women in the Central Asian art and music scene in CEE should not be understated. As a collective, Davra has a focus upon female voices, with previous pieces such as ‘Her Gaze: Moving Image from Central Asia’ (Vleeshal Centre for Contemporary Art, The Netherlands, 2024), and ‘Taming Waters and Women in Soviet Central Asia’ (Biennale Matter of Art, Prague, Czechia, 2024) centring women within a Central Asian context. Unfortunately, however, being a female DJ is still difficult in the region, as cultural pressures to raise a family, alongside unprofessional behaviour from men create a work environment that can feel unwelcoming.

In Riga, the Sublimation collective, co-founded by Sabinē, has found perhaps the widest audience. Sabinē’s time at DJ school in Latvia gave her the curatorial space to experiment, laying the groundwork for a festival that could bring those ideas back home to her native Uzbekistan. Sublimation’s 2024 festival invited DJs from Lithuania to Ukraine, to work alongside their Uzbek counterparts in bringing electronic music at a scale to Tashkent. Their 2025 festival, meanwhile, has gained support from the British Council and is aiming to become still larger in scope. By fostering these cross-border collaborations, both within Central Asia, and between Central Asia and CEE, the festival helps to challenge static notions of cultural identity, as musicians blend strange and exciting protean forms.

Conclusion

It is impossible to succinctly summarise the tapestry that is Central Asian Electronic music and its relationship to the CEE region, and maybe it is a fool’s errand to even try. The collaborations that have been briefly outlined here show that this music goes beyond festival curiosities and world music token gimmicks; instead, we are witnessing ongoing dialogues between the dusty decks of a Tashkent rave, and the sticky floors of a Prague warehouse, where I still sit sipping tea. The girl next to me is from Bukhara and we talk about how there is beauty in this musical exchange. She compares producing a track to weaving on a loom, her soundscape a carpet she packed, unfinished and brought to Central Europe. Each colour is a place she has been, and her heart ‘a thread woven in time to a techno beat’.

Cover image by Joe Walford.