What ‘Mambetka’ means for Kazakhstan in the Age of Inequality

Walking home through the streets of Almaty as a young girl, I remember seeing a girl with the most beautiful hairdo pass by. As was the style in the early 2000s, her head was covered in dozens of butterfly clips. It also followed an intricate circular pattern, and every clip on her head was a colour of the rainbow. My young and impressionable mind was so fascinated by what appeared to me as bold and elegant fashion statement that I instantly started to plan a craft project of my own.

The minute my mom unlocked the door I ran off into my bedroom and started constructing my masterpiece. I wanted it to be even better than the hairstyle I saw on the street, so I decided to grab all the elastic bands, hairclips, headbands, scrunches and butterfly clips that I could find – and arrange them intricately in my hair. To complement the look I put on my puffiest, pinkest and snarkiest ball gown and a feather boa. With a proud posture and my head held high, I descended into the kitchen to showcase my magical creation to my parents.

Nowadays, calling a person from a village Mambetka is one of the many ways that urbanites reaffirm superiority over rural Kazakhs.

“Sweetie, you look like a mambetka” my mom chuckled the minute I appeared in the doorframe.

I slowly realised that my mom didn’t really dig with my avant-garde fashion choices, yet mambetka part of the feedback confused me, I wasn’t really sure what it meant. Although gentle, her mockery brought tears into my eyes as I tried to defend my beloved creation.

After all, what should I feel guilty about? The vision of an angel-like figure on the street with butterfly clips in her hair passed through my mind once again… My posture slowly regained its confidence.

Calmly, as though I knew a secret about life my mom was yet to discover, I deftly tilted my head and said, “Mama, mambetka bolayinshi” — “Mom, let me be a mambetka”.

Years later I uncovered the reason this story from my early childhood became a go-to anecdote in the family gatherings. You see, mambetka, or a mambet for males, was (and still is) a slur that so many of the sophisticated city gals and guys call people from the village. The term became popular during the Soviet rule and was enforced by the government as a way to segregate Kazakhs to educated and uneducated groups.

Nowadays, calling a person from a village Mambetka is one of the many ways that urbanites reaffirm superiority over rural Kazakhs claiming that so many of the so-called mambets don’t have the “city smarts”.

No one in their sane mind would choose a status of mambet by their own free will

But some villagers come to the city and discover an immense variety of products modern capitalism provides, it becomes an overwhelming experience; speaking Kazakh on the daily makes it their actual mother tongue, unlike the urban majority, for whom Russian is their lingua franca.

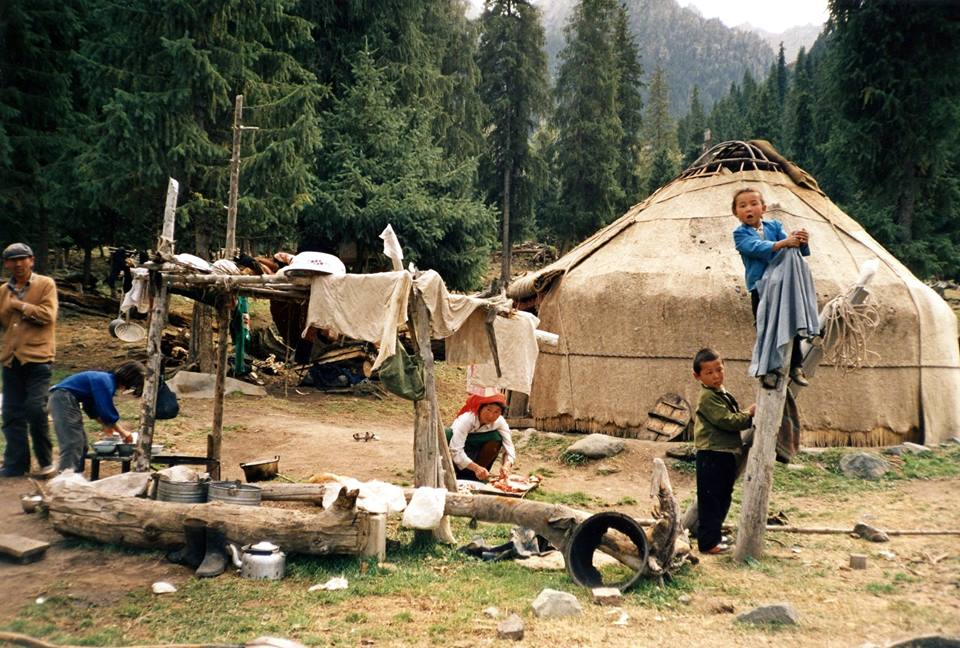

Growing up in the Kazakh steps, caring for the cattle, riding horses and cherishing tradition – they seem out of place in the stone-cold concrete jungles of the city. Hence, mambet in Kazakh society is synonymous with “bad taste”, “bad language”, and “bad manners”.

No wonder that the playful acceptance of the mambet status coming from the Almaty’s finest seemed to be so…. funny. No one in their sane mind would choose a status of mambet by their own free will because it almost guarantees job discrimination and a constant state of negligence in the hierarchal system of Kazakhstan. Yet, we – the alleged intelligentsia – uniformly ignore that none of the mambets chose their status of economic and social disadvantage; rather, they were born into it.

And yes, poverty and inequality are different, but they are much like the “Buy One – Get One Free” deal – they often go hand in hand. According to the United Nations “inequalities in income distribution and access to productive resources, basic social services, opportunities, markets, and information have been on the rise worldwide, often causing and exacerbating poverty.”

So what if my curious five-year-old mind unknowingly discovered a secret? Imagine living in a world, where instead of dividing ourselves and reaffirming superiority over mambets, we would actively choose to work together.

This pattern can be observed directly; from unequal distributions of school funding across regions – to higher poverty rates in rural regions when compared to urban ones. In fact, this poverty gap is so prevalent that according to an IMF report, the share of people with an income below the subsistence minimum in 2014 varied from 1.7% in Astana, the country’s capital, to over 10% in south Kazakhstan, a predominantly agricultural region.

As I dive deeper into my research I uncover that this hostile behaviour towards rural populations is not unique to Kazakhstan. On its Eastern border lays a country, wherein Hukou, a household registration system, lawfully restricts access to each city’s educational and healthcare system if an individual happens to have been born in a rural area.

For China’s economy these migrants are essential as they account for half of urban workforce and create half of country’s GDP; yet, they are the most marginalised and vulnerable group of the population. Meanwhile, India has adopted the most recent addition to its post-colonial caste system based on linguistic discrimination; universities, government jobs and corporate sector all require fluency in English, yet only the ruling elite and middle class can afford to send their children to private English schools.

‘Divide and conquer’ they say — and it seems as if the elites of the world are employing this technique to create artificial privileges. The go-to mambetka bolayinshi anecdote seems innocuous at first, yet its meaning in a broader context of marginalization has far-reaching implications. So what if my curious five-year-old mind unknowingly discovered a secret? Imagine living in a world, where instead of dividing ourselves and reaffirming superiority over mambets, we would actively choose to work together to ensure that no one has to suffer from the economic disadvantages that lie behind “bad manners” or garish hair-clips.