Creative Bishkek: Maksat Sydykov is the first interview of the series introducing the lives and work of talented and creative people from Bishkek, who are helping to establish Kyrgyzstan’s capital as the region’s cultural hub

‘I am trying to bring the world here’ – Maksat Sydykov reflects on his role in the world of contemporary Kyrgyz ballet.

Maksat Sydykov is a Kyrgyz choreographer based in Bishkek, who has performed in ballets for many of the world’s leading companies. He is currently also the head of the Kyrgyz public foundation Pro Art, which supports art and culture in Central Asia, especially in Kyrgyzstan. While at Pro Art, Sydykov has been responsible for putting on several ambitious productions, such as Romeo and Juliet by Prokofiev and The Nutcracker by Tchaikovsky.

Since Pro Art’s launch in 2016, the foundation has invited many of the world’s leading choreographers to the Kyrgyz capital. Due to financial limitations, many young Kyrgyz dancers are unable to travel, and so Sydykov set out to ‘bring the world to Kyrgyzstan’. After many years of experience studying and working in the UK at the English National Ballet and Europe, Sydykov decided to return to his native land to ensure that Kyrgyzstan’s next generation of artists would stamp their mark on the world map.

How was your experience studying in London and how has it affected your career and later creative projects?

Studying in London was a great experience. The city really opened my eyes to a lot of things, which was in large part to its being alive 24 hours a day. It is a fantastic cultural hub and I was fortunate to see a lot of great premieres, shows and museums. London showed me the size of the world and how much is going on and it definitely allowed me to become more creative and open as a result. This has definitely influenced my career and subsequent projects.

Thanks to my experience studying in London and working in Europe, I have been able to collaborate with many crazy and creative people, which has especially been the case in Germany. I was never afraid to try new things and try to meet new people and this has also been beneficial to me, through collaboration with many different people you can create something amazing.

This has inspired me with my aspiration for Bishkek. I hope that my city will turn into a small Central Asian Berlin. Berlin isn’t a beautiful city but the people make it special: they provide it its spirit and atmosphere and are the reason why so many people have fallen in love with the city. A similar phenomenon exists in Barcelona and Portugal, where artists have helped create creative hubs. Hopefully one day more people will start to creative small creative spaces in Bishkek and will spark a creative shift in the city – this is why I believe artists and creatives are so important to cities.

What do you see as the fundamental differences in creative education in Central Asia and Europe and what do you see as Kyrgyzstan’s potential in this area?

The English system is very open and teachers in the UK tend to give their pupils maximum freedom to experiment. The focus is on guiding pupils while leaving them their freedom. In Kyrgyzstan, there is an older system where a teacher tells you what to do and guides you within certain rules, which leaves pupils with less freedom. One of my motivations in returning to Kyrgyzstan was to try to encourage young dancers to go beyond this strict system and to try something new.

I want to bring choreographers to the country that can get young artists to experience a different approach. This has been slightly tricky at times as some of the young dancers are very young – only 16 or 17 – and are often, as is common in Kyrgyzstan, somewhat shy and conservative. The artists are very talented and driven, however, and thanks to the internet and the region’s internationalisation, people in the region have started to become a bit more open, as they can see what’s going on in other countries.

I do however think that Kyrgyz young people could do with more international experiences and a more open mindset. Sadly, due to the region’s economic situation this is not possible as many people cannot afford to travel. As a result, I am trying to bring the world here.

Will Pro Art continue to focus on Bishkek or are you looking to expand into other areas?

We will just stay in Bishkek for now. It is a young foundation and so we should focus on turning it into a success here for now. If the programme goes well, I think we can and should look into expanding, though. I would like to move it into Uzbekistan, for example, which has an even more conservative culture than here. The focus for now is on Bishkek though.

How do you fund the foundation?

I stage ballets in different parts of the world and get paid for them. I then use this money to help fund the projects here. I also sometimes get support from friends. Sadly, supporting the arts is not so common in Central Asia, unlike in the United States or Europe, and so it can be a struggle sometimes, but we get by.

What success has the foundation had so far?

We have staged a lot of productions already and have always used dancers from the big ballet school in Bishkek, which has around 400 students. We always try to work with people that want to be artists in the future, to help further their careers and provide financial support. We have staged some more classic productions, like Romeo and Juliet and the Nutcracker, as well as more contemporary pieces. Sadly we have had difficulties raising money for the project at times, such as when our ambitious charity gala, for which we invited 14 of the world’s best dancers, was unable to raise any money for future productions. The Swiss embassy really helped a few years ago and thanks to their funding we were able to fund future productions.

In general, is there a lot of support for what you are doing?

I think so, yes. People like what we are doing but we can’t always ask supporters for money and so we need to work towards becoming self-sustainable. That’s why we always try to reinvest the money we get from ticket sales into new productions. It will take a few years for major productions to be financially viable and so I want Pro Art to work and I want it to be sustainable. I want more financial support for the project but it is working well so far.

How much of an impact has your strategy of ‘bringing the world to Bishkek’ had?

It has been crucial. I am currently the only modern choreographer in the city and modern dance does not really exist in Kyrgyzstan. I am also the only Kyrgyz, as far as I’m aware, that has worked in big international companies, such as the Deutsche Oper, and so nobody else has the required know-how here. It is thus also difficult to form local partnerships with other groups, and so most of our local collaborations have been with local designers, costume makers and composers, rather than other dance groups.

It was a slight shock for the dancers, as well as the audience, when I started to introduce contemporary dance into the repertoire. In the Soviet Union, the priority was always classical ballet and there was never any experimental dance, a legacy that has carried on. As a result, it was a challenge for dancers initially, as you have to move differently in modern and contemporary dance. A good case in point was when I invited choreographers from New York, Switzerland and Germany for a performance. Their creativity and freedom in the studio shocked the dancers initially. The dancers were taught to listen to the music and to use objects to really go into the piece – they were all trained dancers but had never done anything comparable. The effect was remarkable, especially mentally. Their level improved by 200% after and it has also enabled them to become better classical dancers, funnily enough.

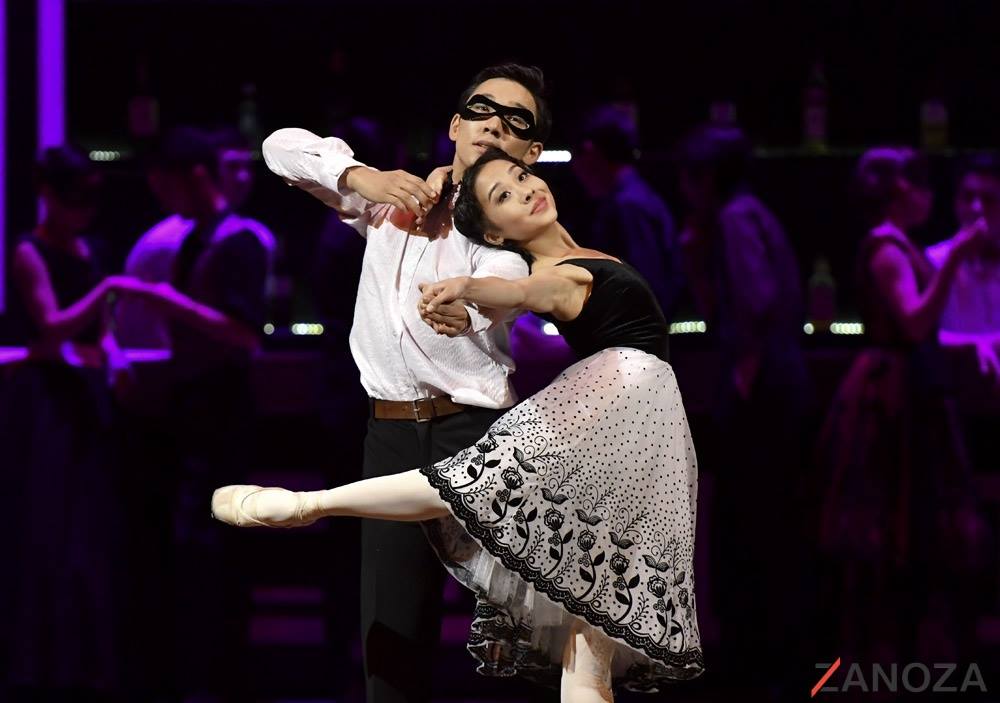

Romeo and Juliet staged by Pro Art

Do you know many other people that have spent many years abroad that have then gone back to launch their own projects in Bishkek?

Not many unfortunately. Most people that leave Kyrgyzstan want to stay abroad and don’t want to return. I do love meeting the rare exceptions, however. If you return to Kyrgyzstan you tend to do so because of passion rather than money, due to the country’s tricky financial situation.

My parents always ask me why I come back for example. I had a good salary and the freedom to travel everywhere and I worked hard for many years to get to that level. I didn’t come back to Kyrgyzstan for the money but rather to do something good for my country and the country of my ancestors. I want to help it develop. I want my children to be in a prosperous, nice, friendly and open country and I feel that it is partly my responsibility to create this future Kyrgyzstan for the next generation and I wish other Kyrgyz would think about it in the same way.

Is there a brain drain away from Kyrgyzstan? How could this situation be improved?

Certainly. In Kyrgyzstan there is not an equivalent of the Kazakh Bolashak programme, where students receive funding to study abroad on the condition that they return to the country for five years after. This could be a good programme for my country also – if you want prosperous, creative and driven youth they should explore the world and learn abroad and then return and share this information with everyone else.

Luckily I do feel that the country is becoming more international – more people have started to come and the country is becoming more open. The youth here is hungry, people want to learn and become part of the global society. This is in large part thanks to the internet – they want to see what the world is like in other countries and are now also global citizens and want to see what happens elsewhere.

There is also always a difference between urban and rural areas and so I want Pro Art to start to expand into rural areas, as they are often neglected. Then youth can also see what happens in cities. In general, I have a positive outlook for youth in the country though. I work a lot with them and have noticed that they don’t need a lot and are happy – I just think that they need to choose a good profession and focus their attention on this.

How easy is it to run creative projects in Bishkek?

I don’t see many barriers. There is a very open youth culture, young people just need to get involved in projects – once they get involved in projects they can follow their own dream. This approach has been successful at Chicken Star, a local Bishkek restaurant, where the youth are encouraged to launch their own projects after Chihoon, the owner, has trained them. This is why he is so popular, as he helps a lot of people develop through a kind of employee educational programme. People in Central Asia need an environment like Chihoon’s.

*answers have been lightly edited for readability