-

Secularism under siege? The State, Media and Religion in Kyrgyzstan

Ana Ross, a student at the University of St. Andrews, explores how in spite of Kyrgyzstan’s constitutional secularism, religion has, on occasion, impacted policy-making in an environment of increasing hostility towards the freedom of religion.

-

Jewish Communities in Kyrgyzstan During The Second World War

Claudia Macey-Dare from Charles University, Prague explores the history of Jewish communities in Kyrgyzstan.

-

Evaluating Central Asia’s ‘Golden Age of Arbitration’: Prospects for a New Legal Age of Commercial Dispute Resolution

James Hone, University of Cambridge, explores the development of international arbitration institutions across Central Asia.

-

How Kyrgyzstan’s new flag design serves as a litmus test for the health of its democracy.

Tom Fort from the University of St Andrews reviews the recent changes to the Kyrgyz Republic’s flag and what this means for its democracy.

-

What role can Britain play in Central Asia?

Peter Molloy, undergraduate in Modern Languages at the University of Cambridge, discusses Britain’s potential to play a positive role in Central.

-

A New Era of Accessibility: How the Internet is Helping Disabled Kyrgyz Citizens Bridge Barriers, and their Ideas Cross Borders

Gunner Bauer, a recent graduate of Lawrence University, explores how the internet has benefitted disabled Kyrgyz citizens.

-

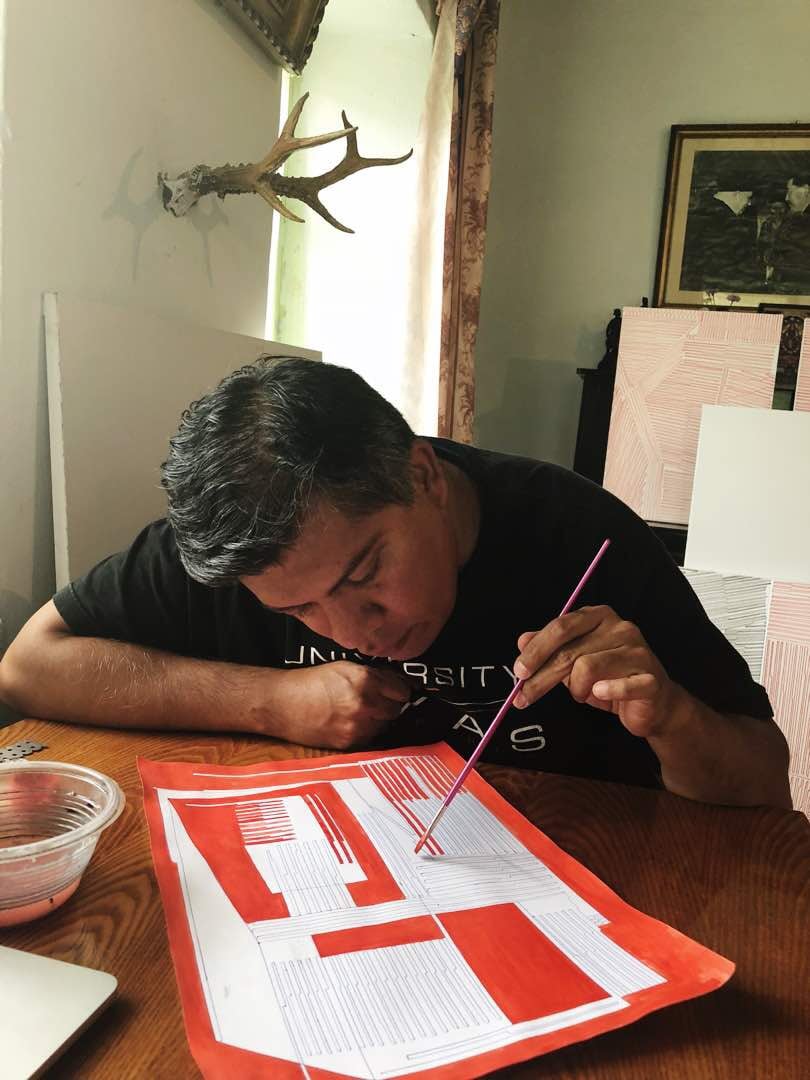

Creative Bishkek: Rafael Vargas-Suarez

Vargas-Suarez Universal , is a contemporary artist based between New York and, for the last three years, Bishkek

-

Creative Bishkek: Group 705

For the latest interview in the Central Asia Forum’s Creative Bishkek series; meet Group 705; Kyrgyzstan’s answer to the Situationist International. Marat Raiymkulov is a Kyrgyz artist who has been involved in Bishkek-based art collective Group 705 since its inception in 2005. Drawing on an absurdist philosophy, the group is primarily concerned with animation, drawing,…

-

Creative Bishkek: Ulan Djaparov

CAF interviews Ulan Djaparov, the godfather of contemporary art in post-Soviet Bishkek.

-

Creative Bishkek: Chihoon Jeong

‘I saw Bishkek as an unfilled linen canvas; one that I wanted to paint on’. Chihoon Jeong is a South Korean entrepreneur based in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. His Korean chicken restaurant Chicken Star has quickly established itself as a creative hub in the city, with regular cultural events and local art on the walls (including works…

-

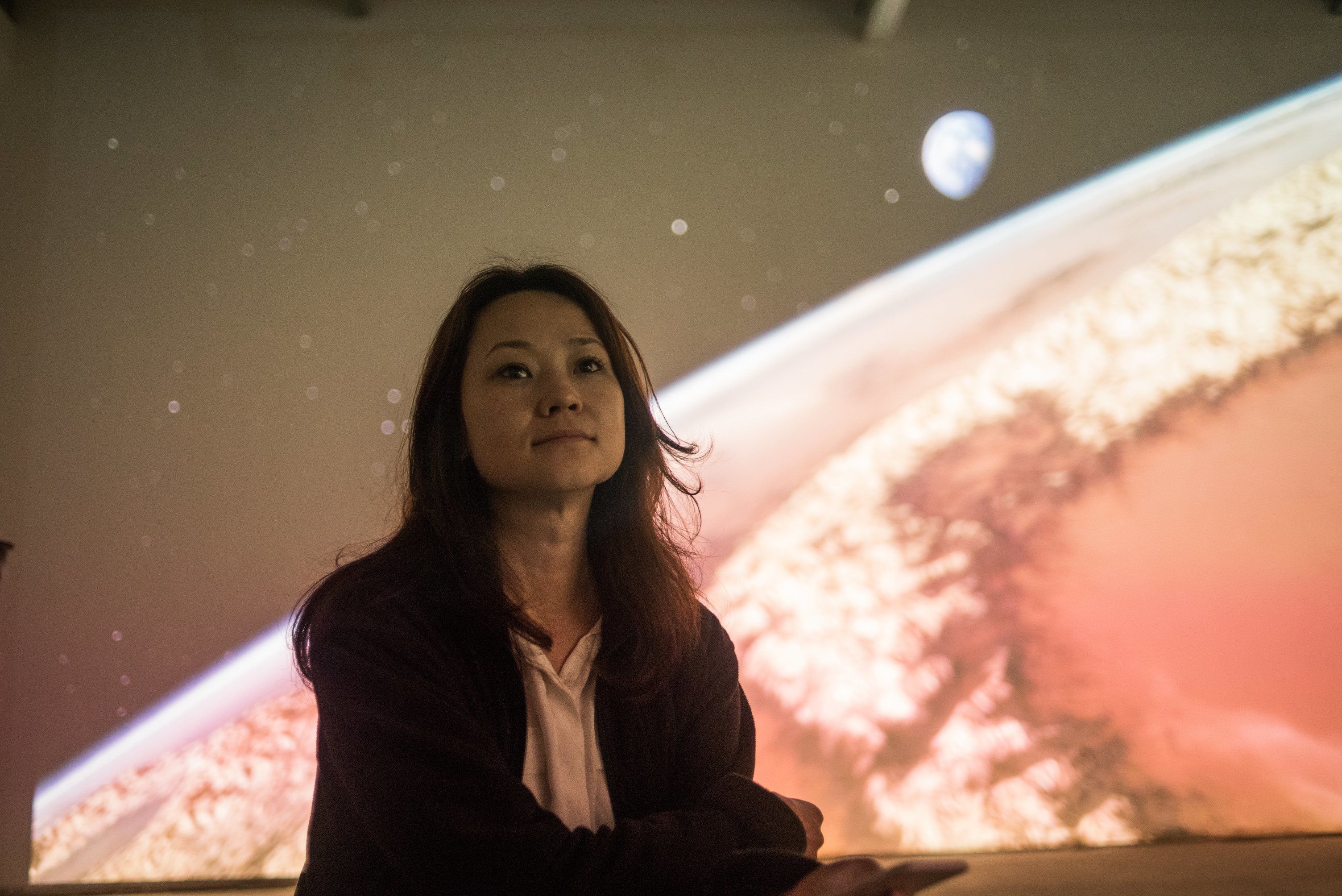

Creative Bishkek: Aida Sulova

Creative Bishkek: Aida Sulova is the second interview of the series introducing the lives and work of talented and creative people from Bishkek, who are helping to establish Kyrgyzstan’s capital as the region’s cultural hub Kyrgyz artist and curator, Aida Sulova, developed Bishkek’s leading art centre: Asanbay. She has helped produce public art in the…

-

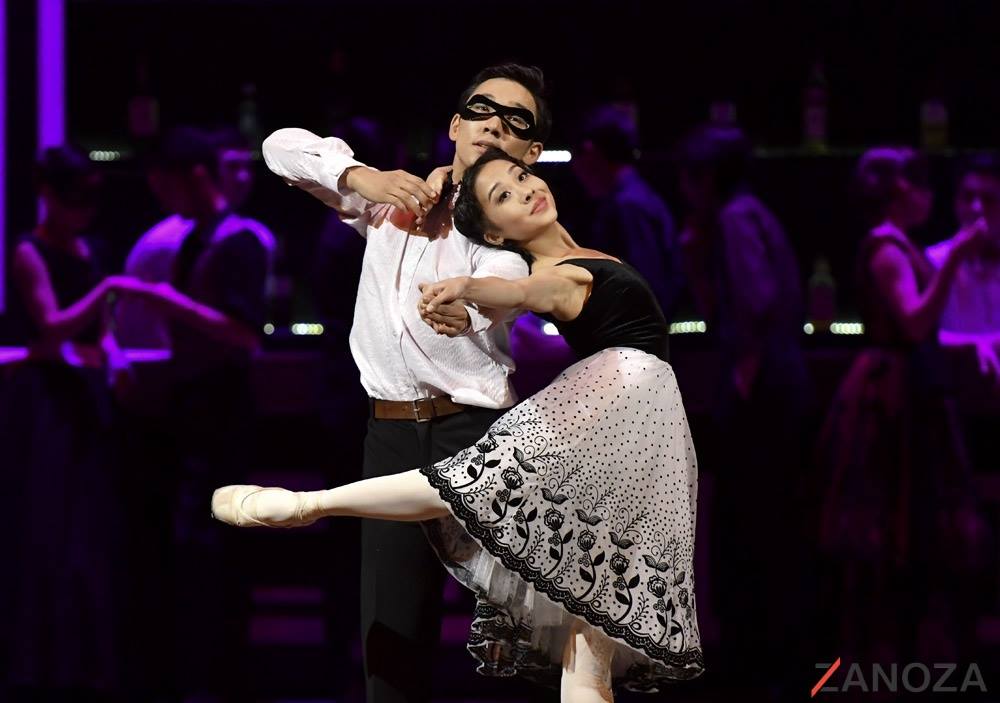

Creative Bishkek: Maksat Sydykov

Maksat Sydykov reflects on his role in the world of contemporary Kyrgyz ballet.

-

Walking in forgotten lands: conservation in Kyrgyzstan

The rural climbs of Kyrgyzstan are legendary. They are also under threat. Brett Wilson has been working as part of an international effort to secure the future of Central Asia’s unique native flora.