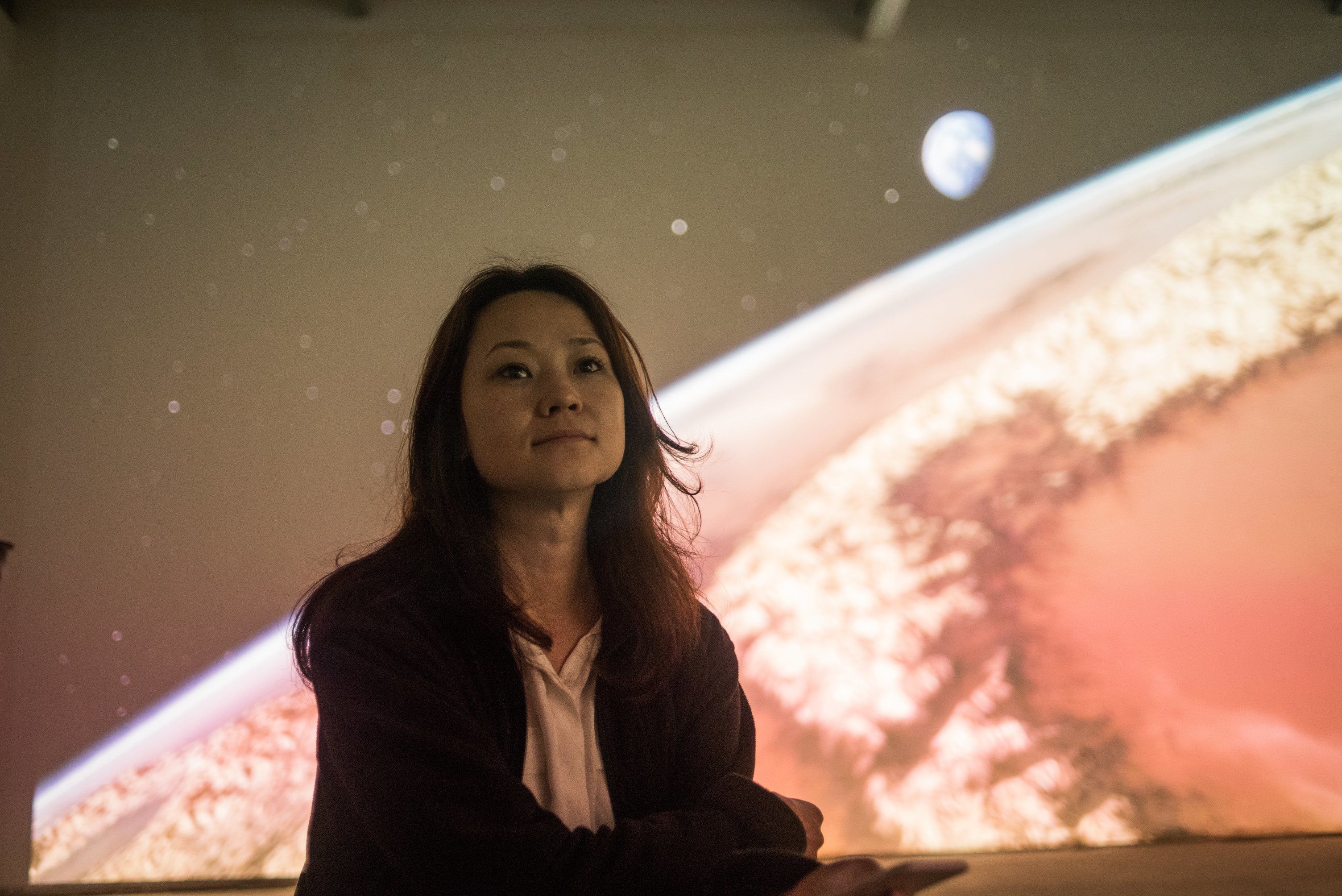

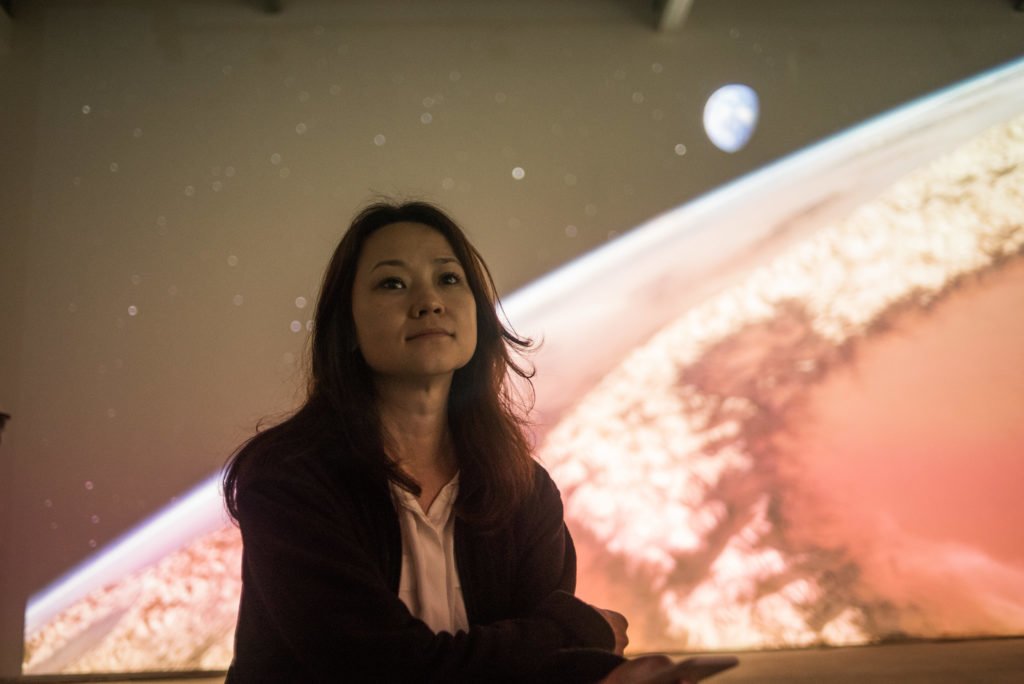

Creative Bishkek: Aida Sulova is the second interview of the series introducing the lives and work of talented and creative people from Bishkek, who are helping to establish Kyrgyzstan’s capital as the region’s cultural hub

Kyrgyz artist and curator, Aida Sulova, developed Bishkek’s leading art centre: Asanbay.

She has helped produce public art in the Kyrgyz capital and been involved in art education in the city. She is currently working in New York.

How did Asanbay originally get created and what have the early challenges been?

I returned to Bishkek after finishing my undergraduate degree in New York and soon after I started working for Henry Myerberg, HMA2 Architects, who is the architect of the new campus of the American University of Central Asia (AUCA), in Bishkek. While at the AUCA, I was engaged in a public art programme with local curators and artists, in this time we produced a number of pieces and had an exhibition curated by Ulan Djaparov. This was how my engagement and collaboration with local artists started. Not long after this, I was approached by local entrepreneurs and investors in the development and restaurant business who showed me a 1800 square metre space, which they intended to use for a brewery business with a dance space. My proposal was to found a flexible multi-purpose place which can transform its space and resources for various events. The main activity of the Center are a strong art and education programs that are supported by side commercial activities such as a restaurant and event hall. This was the original idea for creation of multi-disciplinary Asanbay, which now has event spaces, a gallery and a Georgian restaurant.

The mission of the center is to be a flexible space for art, education, and entertainment programs for communities to enrich their cultural life. However, not everyone reacted enthusiastically after we opened Asanbay. Some people, for example, accused me of commercialising art by making it too accessible and by serving food and drink in an art space. After I explained to them that most museums in the world work like this, and have an additional entrance fee, they started to listen, so I think it’s mainly a cultural thing. People need to understand that due to the cost of production and rent, it is only possible to have free exhibitions alongside these commercial activities.

Asanbay is but one of Bishkek’s many exciting new creative projects – do you think the culture of the city is changing and where do you see the city heading?

There’s been a dramatic change in the last couple years and I see it as largely positive. There is a real thirst and strife for a better life and the civil community has become much stronger in recent years. There are now lots of people who are launching their own creative projects and the city’s start-up culture is improving. There is now even speculation that Bishkek is becoming the Berlin of Central Asia. My only concern here is that there is no central vision or mission, so I hope the younger generation will be able to provide this. I really hope that education and culture are seen as priorities – culture is so underestimated in my opinion and I think it is really important for people to understand that it is an effective tool to bring social changes.

I think collaborative initiatives are extremely vital – and not just from artists, but also from businesses, the government and the creative community. I’ve already seen the challenges involved in these initiatives at the Asanbay centre, as people often have conflicting interests and ideas. Nevertheless, as Asanbay shows, such collaborations can produce very positive results. I’m also happy that there are more initiatives like co-working spaces, urban talks, research labs, etc. and that people in culture are starting to bring international artists, curators, and art managers to the city. Cultural exchanges such as these are groundbreaking and so I think the city is heading in the right direction, all things considered.

How different is the process of being an artist in Central Asia compared to Europe or the United States?

The contemporary art scene is strong in Bishkek and I can see the thirst that artists in the scene possess. Artists there are constantly producing art and the fact that there isn’t funding and support isn’t really an obstacle for them. An artist in Kyrgyzstan is an artist, whereas an artist in the States is an artist, manager, curator, specialist and PR manager – as such, artists in New York have much more knowledge about the art market and they are more experienced in promoting themselves. I think this is about survival though – the context in Kyrgyzstan is different as artists there are less focused on personal promotion. It is probably more genuine in Kyrgyzstan and their message is stronger. I have tried to promote some Central Asian artists by making websites for them – not everyone understands the value in this though.

Do you think Central Asian artists will soon start to have this broader defined set of attributes?

Surprisingly, it is the older generation in Central Asia that have started to get involved online and especially on Facebook. There are now artist groups like the Central Asian pavilion of contemporary art – this shows that there has been a shift. Younger artists have increasingly started to self-promote on Instagram also. This is of course largely about economics and it is generational. What makes Central Asian contemporary art different from the rest of the world is that artists in the region are not forced to come up with an issue because the issues are already all over – social issues, personal issues, gender issues. The artists there truly reflect openly and freely and this is channelled in their art. Most of the work I see at Art Basel and the Venice Biennale, for example, strikes me as lacking substance or a strong idea, which I don’t often find in Central Asian contemporary art.

Have you personally curated any Central Asian artists to show them to a broader audience?

I have a foundation called “Kachan?” (translated from Kyrgyz as “When?”) and through this I managed to bring a few Central Asian artists to Washington a couple years ago. In Washington, there is little cultural knowledge of Kyrgyzstan and so I wanted to display the works of two provocative artists from the region – one was about the revolution and was called the ‘Kinematics of Protest’ by Eugene Boikov, while the other was called ‘Perestroika’ by Shailo Djekshenbaev . This was the start of my cultural exchange programme.

What other projects have you been working on recently?

A few years ago, I did quite a few urban art projects on the street – as I didn’t go to art school and am not trained I prefer these kinds of projects to more classical gallery pieces. One of my major projects was about how people react to surprises on the street and in the city environment, an idea which is known as hijacking the space. For example, I decorated trash cans and bus stops in Bishkek as a response to the city’s garbage problem.

I’m also currently working for an architectural firm, helping on projects in both Kazakhstan and in the States, which I have been doing for a little while. Recently, I have started working on a project to change the role of libraries in Bishkek, which I see as really important. The library has changed its role and has become more of a community centre. As a result, librarians can become more like curators and event organisers – people who provide more knowledge than just giving out books. I find this especially important as Bishkek’s libraries are empty currently, even though they could be used by new startups, for example, who currently rent expensive studios in order to be more like Silicon Valley startups. I’m convinced the role of libraries can be enlarged and they can be used to create a stronger and happier community.

Have your projects been particularly inspired by any cities you’ve lived in or visited?

Of course my projects have been inspired by places I’ve visited but I do think that most of my ideas are fairly universal, rather than geographically bound. People will say that I copied the idea of Asanbay, but every large city has an art centre with activities. The concept behind Asanbay was naturally also influenced by experiences I have had in New York, Berlin and Tbilisi.

On a more personal note, leaving to study in New York had a major impact on my outlook and personality. I like the fact that I was able to express myself the way I wanted there, which hadn’t been the case before. In that sense, I was able to follow my own American dream. Nevertheless, I always felt that I wanted to return to Bishkek, in order to help develop the city. The international experiences I gathered before returning were crucial in knowing how to enact positive changes there.

Any final comments about Bishkek’s future and its creative scene?

When I talk about my country, I don’t want to talk about it in black and white terms – it’s cool and it’s doing well but sometimes it gets the wrong leaders – I am however hopeful for the future and think we’ll see more positive changes soon.