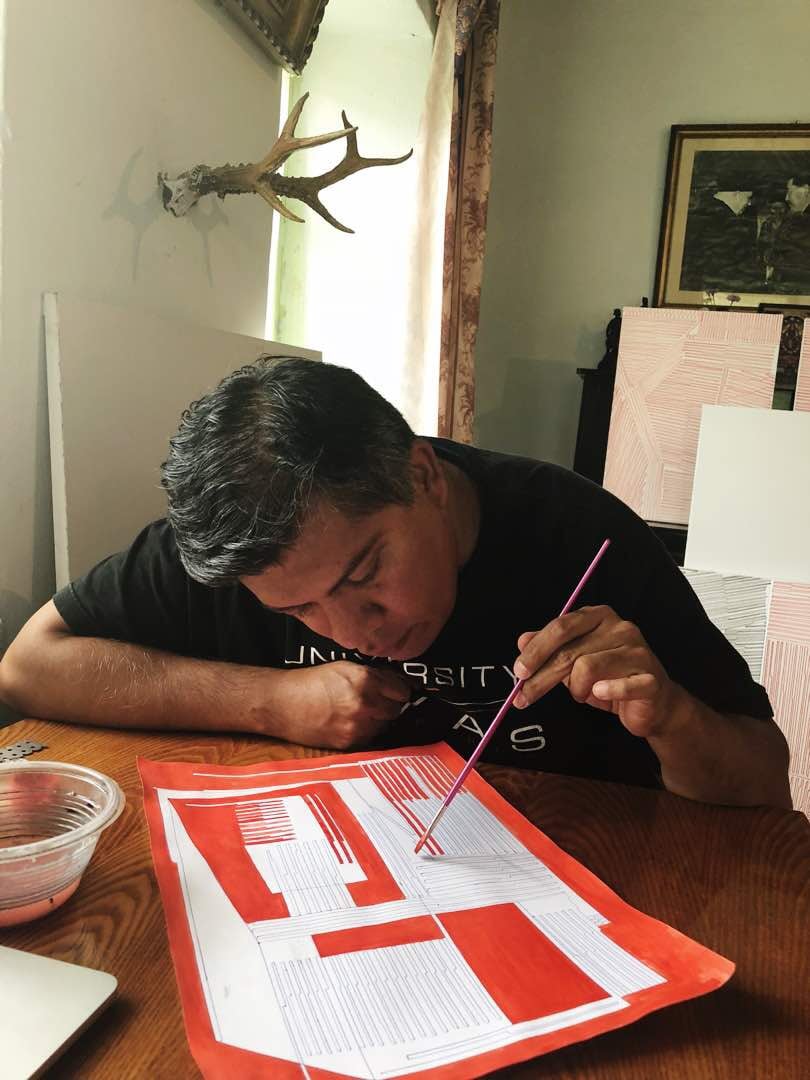

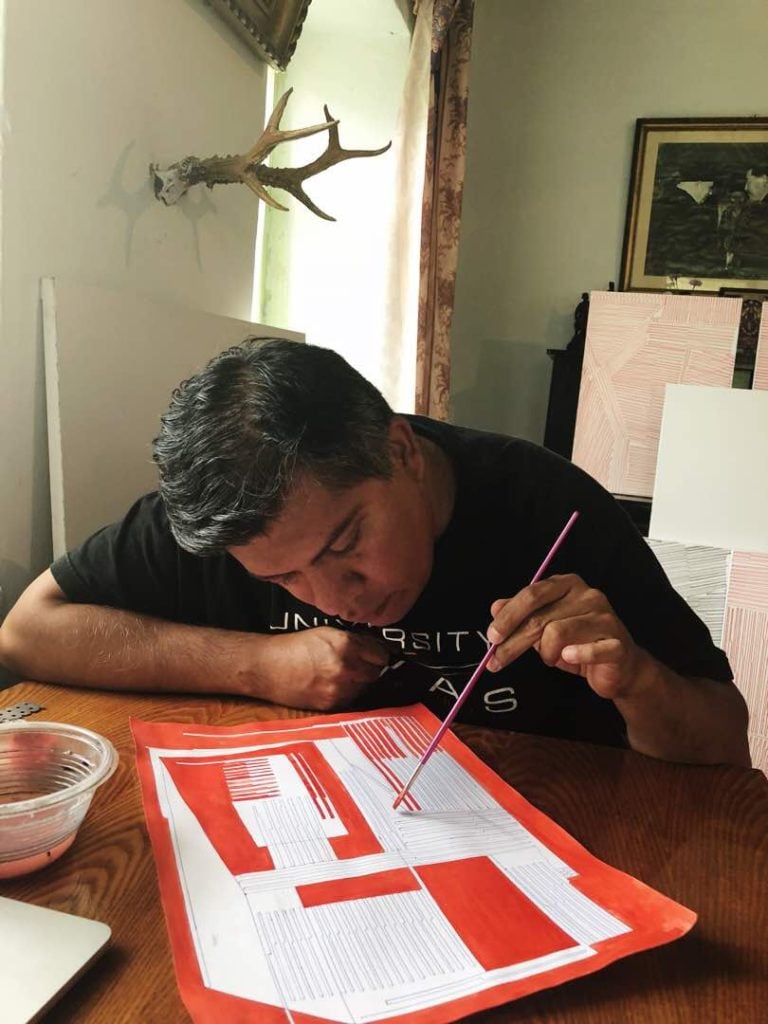

Rafael Vargas-Suarez, also known as Vargas-Suarez Universal , is a contemporary artist based between New York and, for the last three years, Bishkek. His work, which is based on the visualization of scientific and technical data, has been featured in numerous museums and galleries, and has been the basis of his many collaborations with institutions, governments and universities. Recently he has been exploring the history of materials, from traditional oil painting to experimenting with materials typically used in spacecraft and materials sciences. This was also the inspiration behind his moving to Bishkek: for the past few years he has been learning to work with ancient textile materials such as silk and wool. In Kyrgyzstan, he has found the perfect environment to learn techniques and their history from local masters, as well as doing experimental work with them.

What originally influenced you to start using these more traditional materials?

Over the last 15 to 20 years I have been doing a lot of artwork referencing, for example, networks, microchips, visualization of scientific phenomena and subjects related to the space programs of the US, Russia, the EU, Japan and Canada. As I got more aware of complex visualization systems, I started to get more interested in complex architecture, such as microchips. Thus, I decided to go backwards rather than forwards to deepen my understanding, first to adding machines and punch cards, and then later to carpets and textiles, silk and wool. These materials are the great ancestors of what we use today as computers, LCD screens and mobile devices. I started to become interested in the question of how it is that all of these things that are so commonplace today came to be. If you look at any carpet or rug you can see a lineage to today’s more complex electronic devices. Going to Central Asia you actually get to access a lot of these traditions from the craftspeople and communities, whose ancestors created these complex items. The knowledge has been passed down the generations and is still very relevant there. Coming from the US, where I always worked within a very contemporary and conceptual framework and moving into those areas of work and research has been really gratifying.

What led you to finally decide to move to Central Asia?

I was commissioned to make a permanent artwork for the American University of Central Asia. HMA2 Architects are based in New York and had seen my artwork before in a gallery in Manhattan. They approached me to come up with a proposal for a permanent artwork, which I presented 1 1/2 months later. Eight months after our first meeting we were in Bishkek. We went regularly for two years to complete the work. After finishing the commission, I realised that I enjoyed working there and that I wanted to continue exploring silk and wool as well as all other ancient materials and techniques, and wondered how I could integrate them in non-traditional manners into my work. That is to say, I don’t explicitly follow western or eastern traditions. These materials are underrepresented and under-explored in contemporary art – there are some fibre and textile artists that use them but they are usually pigeonholed into a regional or craft category, so I wanted to really do research and see what I could do with these materials in my work.

“34 Blue Vectors” (2017)

Tian-Shan mountains sheep wool & chi reed technique 45.5 x 26.5 inches (116 x 67 cm)

Listening to your comments it sounds like you are more closely involved with traditional artists in Bishkek rather than the city’s contemporary art scene – can you comment on this?

The ‘art scene’ in Bishkek is very small, especially in comparison with New York, where I am based. There are hardly any galleries or museums in the city, so it couldn’t be more different in terms of the cultural landscape and the amount of activity going on creatively. There are however a lot of creative people in the city, both young and old. I’ve noticed that they’re basically divided between those educated in the Soviet system and those educated after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The younger artists definitely tend to be more conceptual and tech savvy. In general, there is however still a huge emphasis on craft and what is called ethno art, which means traditional Kyrgyz or Central Asian motifs, colors and materials for making very lucrative silk road products, which are very touristy. So there is a very vibrant community in with traditional crafts and its markets.

Part of my creative duality in Kyrgyzstan is that I associate with the artists doing super traditional local regional craft work and then on the other hand I try to be a mentor to the younger, more contemporary, artists, who are incredibly hungry for information from the west and other places. I do however make sure to not tell them what to do or how to do it.

Put generally, it can be said that the whole Central Asian region is trying to bring itself into the new ‘western world’ whilst at the same time trying to maintain its ancient traditions. Do you think Central Asian artists are trying to do something similar also, by combining modern methods with traditional techniques, or are you somewhat of a pioneer in this regard?

This is a good question and indeed is something I ask myself almost every day. You see strict divides between people doing traditional things and those doing experimental contemporary things. For example, you are almost guaranteed to make a living with traditional crafts – there is a market there, even a foreign one (primarily American) for their local crafts. Because of local policies in Kyrgyzstan, the artisans producing such goods are actually considered small businesses and are doing really well selling their goods abroad. One thing I have noticed is that these crafts artists are slightly frustrated and often afraid to experiment, as they fear that they won’t be able to make a living and sustain their families if they do so – in effect, they are artists not respected workers.

On the other hand, the more experimental/contemporary-minded artists are very much influenced by western, modern, contemporary ideas and aesthetics but sadly there is very little opportunity there to sustain a living doing that, even as a teacher. They usually have to teach standard western art history, which is a leftover from the Russian traditional academic teaching structures, which are very safe and conservative. There is also a conflict between generations due to differing ideas and intentions: young art students and older traditional professors who were educated during Soviet times are divided. A lot of the younger artists feel frustrated and can’t really do anything with the super formal training that they get. There is however a variety of art collectives, such as MuseumStudio, 705 Group, Kasmalieva & Djumaliev’s ArtEast , Shtab and the very young Laboratory Ci. There’s even LGBT art collectives known as SQ and Labrys. The cool thing about Kyrgyzstan is that you can make art work that specifically is critical of political, social, class and racial and ethnic realities. It’s very important to be free as an artist anywhere.

A major question there relates to Kyrgyzstan’s identity between the east and west and whether there is an identity crisis creatively about what it is to be Kyrgyz. This is definitely an interesting thing to observe as an outsider, as a foreign artist. You see Kyrgyz artists addressing these questions, more so than in other countries in the region, where there is a major lack of freedom of expression. I always explain to young artists in Kyrgyzstan that they are living in a democracy, even if they don’t realize it. Yes, it’s a young country and underdeveloped, but fundamentally they are young artists in a democracy and can express anything they want, it’s their legal right to do so. This is the real difference between artists in Kyrgyzstan and in Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan – in Kyrgyzstan nobody is going to shut you down for criticizing – people may tell you not to, but you won’t be arrested for it. An even bigger tragedy in neighbouring countries is artistic self-censorship, which is clearly a tragedy and leads to arrested development as far as developing identity and national culture. This does not mean that critical contemporary Kyrgyz artists can sustain themselves, however. This entire panorama is of course truly interesting to me as a western artist. I make sure to not step on anyone’s toes and I also don’t intend to exhibit or sell my art there, as I’m very sensitive that I am a foreigner and merely observing from the cultural side lines while I produce my work there.

Let’s carry on with that point. You are a foreigner and are trying to enact a change in Bishkek and the wider region’s art scene. Has this been difficult for you in terms of getting contacts or local credibility or has there been a general acceptance and willingness to learn?

There are many challenges in Kyrgyzstan – the primary one being the language barrier, as I am still trying to learn Russian and only understand very basic Kyrgyz. There are however lots of young creative people that speak English, as a few have been educated abroad. Overall, in Bishkek, I can also get by with my limited Russian – I have an assistant to help me, however. Another challenge is that people there are often very insecure, especially young artists, as they come from very traditional and conservative families, which means the idea of being an artist is frowned upon, and there is very little understanding of it, which is the opposite of my background, where the system I grew up in fostered and supported the idea of being a player in a cultural landscape. It happens frequently that I have to explain and basically define what I do, as people there often don’t fully understand it, which was quite surprising to me. More often than not, people in Central Asia are quite surprised that I make my living as an artist.

I have started to hire assistants, mostly younger artists that are not sustaining themselves with their art. We often have great conversations in the studio about lots of topics and they do tend to get a lot of confidence when I tell them how it is that I got to become an artist and what my vision is for the future. They are not used to people being so open and generous and so they are very surprised and ultimately appreciative when someone opens up and gives them advice. Unfortunately jealousy, territoriality and a tribal mentality are quite common, which can clearly be detrimental to their progression.

As far as breaking into the scene, it should be noted that there isn’t really one. I’m also mindful of the fact that I’m just there to produce, to do my work there and then it gets exported back to the US. People often ask me when I’m going to do a show there but I don’t have any plans for that and I don’t think local curators intend for that to happen either. At the start of my project at AUCA, I felt a jealous energy around me by some of the local older artists, as they saw the project there as a great opportunity that was taken away from them by a foreign artist. However, one of the objectives of the public art initiative, was to bring an artist from the US to do something there. There were people complaining at the start so the architects and president of the university decided that it would be a good idea for me to collaborate with a local artist on the project, so I chose to collaborate with Dilbar Ashimbaeva, of Dilbar Fashion House. She is the most respected fashion designer from Central Asia. She educated me about silks, embroidery, fabrics and really gave me a crash course on how to work with silk for my art. She is a master and has travelled all over the world to do her work. At the same time, I educated her a lot on contemporary art, conceptual art and installation art, so it became a great creative partnership. We even became great friends and have even made some silk paintings together more recently.

Overall, Kyrgyzstan is a place of production for me though. I have learned so much there, not just about Kyrgyzstan and its art but also about myself and the artistic traditions that formed me. More and more I feel that it’s a place I can contribute to more as a mentor or educator. Last year the American embassy and several NGOs have asked me to help develop art education programmes for the public and for children. I always say ‘yes, absolutely’ to any possibility with arts related education. I find it incredibly important and early education is how real impactful change happens.

Are you the only foreign artist in Kyrgyzstan with a focus on production?

As far as I know, there are fewer than a dozen foreign artists that have taken up space and worked there, while a few others are temporarily working there with an NGO or embassy. From what people tell me, I’m the most involved foreign artist ever so far! I have a studio in the mountains of the Southern shores of Lake Issyk Kul and one in the center of Bishkek, so I am very embedded. I’ve made many friends and have started to hire people now so I am now learning who does what and such. I am still more embedded in New York but I’m firmly setting roots in Bishkek too. I like that there are no distractions in Kyrgyzstan, so I can be really focused and work long hours in the studio. I can do so in New York too, but there are so many more distractions and interruptions. Surprisingly, Bishkek can be a little busy and and hectic too, but in general I get a lot of studio work time, so I feel really satisfied there. I tend to be focused wherever I go, but I’m especially productive in Bishkek and at Lake Issyk Kul.

Do you want to stay there for a longer time or do you have a set date for when you want to fully return to the States?

Right now I’m actually in the US but I did just spend 6 months in Kyrgyzstan, and did the year before also, so I’m currently doing half-half. I don’t have a specific plan and tend to be someone that goes with the flow. As long as I can produce there and don’t run into problems I can continue there. I’m lucky that I can work anywhere, as I think most artists can’t, after they get set into one way of working. Because of the nature of my work, I’m always looking for new materials, new ideas, new concepts, research and travel, which is clearly helped by my innate ability to be able to shift modes and adapt to almost anywhere so far. I never actually imagined that I would spend very much time in Bishkek or even having studios there at all, but the AUCA project showed me that I could work there. I still have some projects I want to do there, such as designing my own yurt, making carpets with traditional materials, using the Shyrdak and Ala-Kiyiz techniques for wool.

Your work is primarily at the intersection of aeronautics/astronomy and art – is this something you are still doing in Central Asia or has your focus shifted since you started using more regional materials?

You’re asking really good questions, related to things I think about all the time. As far as the images and resulting artworks that I’m making there and here in the US, I am still very much connected to this idea of spatial movement, as well as astronomical charts and microchips. I’ve also shifted my attention from NASA to Roscosmos, the Russian space programme, whose launch facilities are located in Kazakhstan. It is an interesting contrast to see this rocket infrastructure in the middle of Kazakhstan with camels and people in traditional Central Asian dress. So yeah I can say that a lot of my work is still very much related to geometric abstraction, and scientific visualization. I don’t know how much my work can change thematically or if there is an orientalist or silk road influence in my art. I think the influence is purely material so far, rather than conceptual. One of the interesting things about doing the work I do there is the way people react to it – they associate it a lot with Russian constructivism and pure modernist art, which means they aren’t so confused by it, and more importantly, I’m not confusing myself with it.

So you have been going to Bishkek fairly regularly for the last 4 and a half years. How much do you think the city has changed or modernised in that time, in terms of its creative scene and how people view their city, country and future?

There are definitely many changes to observe and live with. Almost every day in Kyrgyzstan, I see a new idea or project that people really gravitate towards or are very curious about. There’s a lot of potential, as well as smart young people who are really hungry for new ideas and new things. At the same time they are still holding on to their very traditional values so I feel that Kyrgyzstan is culturally torn between conflicting cultural visions of their future. I believe there are three main camps: those that maintain a traditional Kyrgyz structure infused with conservative Islamic ways of life and traditions, those that are attracted to Russian culture, language, mentality, and with a lot of nostalgia for Soviet times; and the camp I am associated with socially, is globally minded and gravitating to new, progressive ideas and developing culture.

I do see a lot of change in general though, and it tends to happen at an increasingly rapid rate. You also see things that probably won’t change, especially when you’re outside of Bishkek. Outside of the capital, you’re not going to see the change, amount of change or rate of change. It’s interesting because there’s a kind of identity crisis – people want to be contemporary and up to the minute but are held back by very strong traditions, so it’s quite a dynamic to see as a foreigner.

Do you see these three camps as split along generational lines or does everyone have all three internalised in them to greater or lesser extents?

It’s mostly generational but then from time to time we’re surprised – by “we’re” I am referring to us few foreigners. For example, there is a huge emphasis on getting married as young as possible, even, at times, in more seemingly progressive circles. So you do see people whom you think are living their lives in some sort of anti-establishment direction with their lifestyle and beliefs, and then suddenly they’re married and wearing the hijab and living a super conservative Muslim way of life and then that’s it. They had their fun, they had their chance, they had their foreign friends and were living their western values and then all of a sudden it’s just cut off. That’s something I’ve seen more and more in the last few years and I’m like ‘wow, what a shift’, one minute you’re a feminist and the next moment you’re married, either by choice, family or tradition, and there’s no going back. It’s not something one sees within the ethnic Russian population. There is definitely a massive emphasis to marry early, in comparison with the west at least, and this means that the divorce rate is very high, so I question the rapid pace of such major decisions being made. I don’t judge but I definitely question them there.

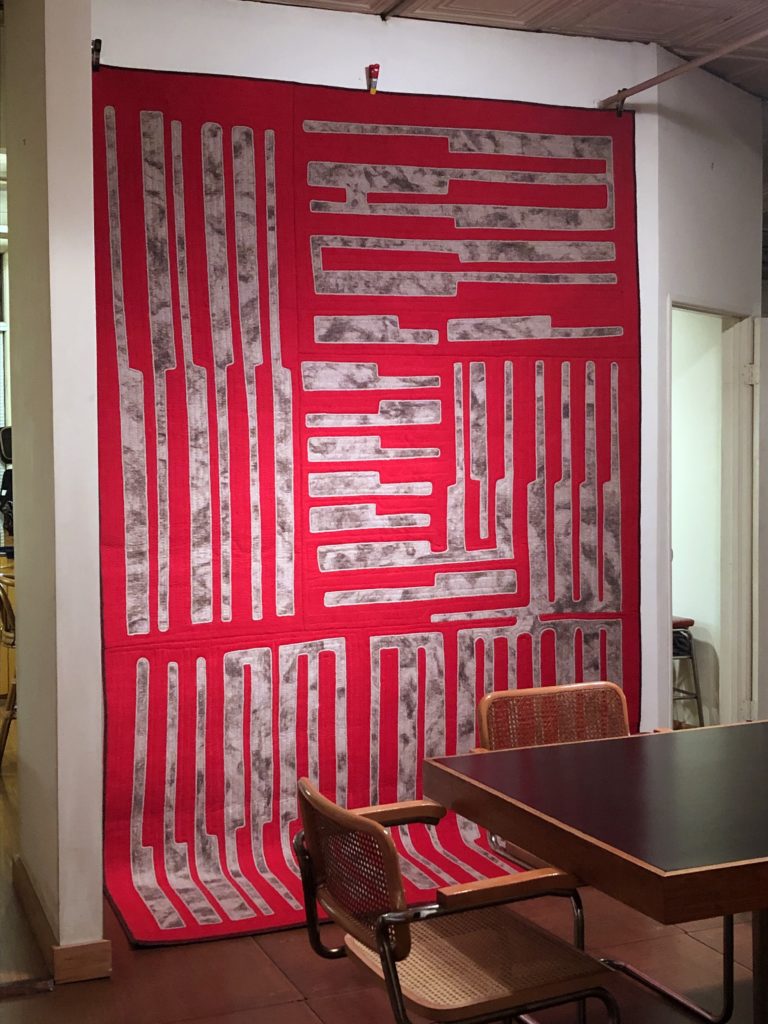

Hand sewn, felted & hand dyed Tian-Shan mountains sheep wool in ala-kiyiz & shyrdak techniques

84 x 134 inches (2.13 x 3.40 M)

Edition of 10 + 2 AP

In which direction do you see the country heading? Is the dominant movement towards liberalisation and democratisation or do you think the more traditional culture is starting to claw its way back in?

That’s something else we all talk about all the time. I have a lot of conversations with people from the US embassy and different NGOs, amongst others, about these trends and socio-cultural dynamics. Everybody knows that this is a very small developing interesting country that is fundamentally a democracy. Evidently, the last elections and the non-violent transfer of power caused foreign government to send some of their diplomatic representatives to congratulate the new Kyrgyz President and his administration. I think the main challenge for Kyrgyzstan at the moment is to stop expecting handouts, and I mean that from the top levels all the way down. There also needs to be a greater sense of ownership, where people commit to protecting what is theirs.

I feel Kyrgyzstan is going in the right direction but there’s going to be a lot of aches and pains along the way. I also think a lot of early education is needed – not just in schools but also at home, as that’s where all education starts. So I think in another generation or so it’s going to be a really interesting place in terms of social standards. I always tell young people that there is no reason why their country can’t become similar to Switzerland or South Korea. I always use the example of South Korea, a country with very limited natural resources that has progressed so much in the last few decades, mainly due to changes in education, attitude and policy to benefit its people. It is also important to note that the Kyrgyz government is secular and that they’re really against the growing Islamisation of the country, so there certainly is a big divide between the secular and Muslim populations, which goes all the way up to government. Kyrgyzstan has this same potential as any developed country, but it will take a while and it won’t be easy. Nothing good is easy, you need commitment at all levels.

Do you have any final comments with respect to your work or Kyrgyz society?

Most people I

speak to outside of Kyrgyzstan haven’t heard of the country when I tell them

that I’ve been working there – many also hear Kurdistan, which is

obviously very different, so I always have to explain where it is and that it’s

not a dangerous place, that it’s the only democracy in its region, with free

and open internet and so on. In a way I’m not just trying to encourage Kyrgyz

people to look into themselves, to look around, to look beyond their

borders, but also people in the States and elsewhere, that Kyrgyzstan and

Central Asia are important and valuable parts of the world. Growing up in the US during the Cold War and

after the collapse of the Soviet Union we knew nothing about the region and

it’s definitely worth knowing about. It has a really interesting history, with

the silk road, nomadic cultures and its vibrant mix of ethnicities and

languages. I have met people there that did ethnographic studies and

anthropological research during the Soviet times and that found Central Asian

connections to Native American migrations. These connections actually exist

throughout Central Asia, East Yakutia and Eastern Siberia. You see these

connections in art, architecture, food, literature, and even in the textiles

and fabrics used in these regions. Sometimes I see textiles that look Peruvian,

Mexican or Navajo. There are many links that both sides are not very aware of

yet. Art is a very powerful tool for anyone looking to connect these

dots. it’s both a great opportunity and a privilege to be able to serve such a

purpose.